Tags

The following provides a disappointing insight into the risks of entrusting even the most trivial of tasks to ‘throughput-biased’ service providers. What do I mean by that term? If your living is dependent on achieving a certain level of fixed-price turnover for a service for which market-dictated pricing significantly undervalues the actual labour required, then it can be a challenge to deliver a service to a consistently acceptable standard. That is no excuse though to abandon any pretence at competence and instead to develop expertise in the delivery of complete slap-dashery.

Some of you may have deduced that I have started to take in a limited number of jobs to keep me busy in this new phase of my life, the first of which documented in the previous post. This present post concerns the second such job, a Seiko SKX007 whose owner reported fogging of the crystal and timekeeping issues.

Superficially, this well-used watch looks presentable but a closer examination of the interface between dial periphery and chapter ring sets off some alarm bells.

A combination of the fogging and the deposition of what looks like copper salts, leeching from the brass dial was strongly suggestive of water ingress. This had been an everyday wearer and the owner had worn it in all conditions and for all sorts of activities including seawater swimming. He also reported that he had taken the watch to a local watchsmith to investigate erratic timekeeping. Following its ‘service’ the owner continued to use the watch as he had previously, but the watch started fogging up following its next immersion in the sea. It took no more than removal of the case back to reveal the cause of the evident loss of water integrity.

The watchmaker had taken it upon himself to replace the substantial original gasket with an undersized, inadequate sliver of rubber – whatever looked approximately up to the task (although quite why he thought it necessary to replace the original gasket is unclear). A comparison between a correct (used) gasket (left) and this sorry excuse for a facsimile is shown below.

The disastrous consequences of this substitution can be seen more clearly if we take a look at the movement in situ, its rotor and second reduction wheel removed to provide a clearer view of the devastation.

Aside from the lashings of grime, presumably imported along with the seawater, we see crystallisation of seawater salts on the edge of the main plate, adjacent to the barrel and some copper salt leeching from the dial close to the balance. We can also see rust around the second reduction wheel mounting post.

The next step is to remove the movement from the case and inspect the dial.

As noted earlier when viewing the dial through the crystal, seawater has clearly been lapping at the dial edge although thankfully not submerging it entirely. Crystallised salt deposits encrust much of the circumference of the dial, most of which within that part that will be hidden by the chapter ring but I will need eradicate this in due course as part of the clean-up. Another look at the train-side of the movement confirms its very sorry state.

The mid-case and chapter ring are similarly liberally contaminated with salt deposits although thankfully there is little sign of any actually corrosion to the steel of the case.

The bezel action is very stiff but in any case the turning ring needs to be removed if I am to give the case the thorough clean that it needs.

The bezel gasket, incidentally, has broken, just as a result of wear and tear.

I will also need to remove the crystal to gain access to the chapter ring and, of course, to do a proper job at cleaning the case. The crystal has picked up its fair share of scratches over the years and could probably do with replacing.

The crystal is secured in the vice-like grip of a black nylon gasket and a crystal press is required to press the crystal out of its confinement.

With that done, the casing parts are ready to be cleaned or disposed of.

Believe it or not, the watch did seem to have a little life in it when it was delivered to me, but with a decent wind on board, it ground to a halt in short order. The movement has plenty of excuses not to run, but I discovered one particularly conspicuous impediment having removed the balance and taken a squint at the interior.

Clearly, the only way to get this movement running is a complete nuts and bolts strip-down but that is simply not economic given the price of a brand new NH36. The original 7S26C movement is therefore a write-off.

Given the salty dial-edge, you may be wondering to what extent the rear side of the dial has been affected. Here’s your answer:

The dial edge sits on a black plastic movement ring which also displays signs of salts contamination.

I have partially dismantled the calendar components of the original movement because I will need the day disk and the movement ring to adapt the replacement movement to the requirements of a crown-at-3:45 SKX007 case. The replacement for the write-off-7S26C is a new NH36A, a movement offering significant upgrades of seconds hacking and hand-wind capabilities.

That grey movement ring won’t fit the SKX007 case and so the first task is to replace it with the (now clean) black item donated by the outgoing 7S26C.

The requirement to replace the day disk is evident if we temporarily refit the NH36A original, its printing alignment designed for cases with their crown at the three o’clock position. The day and date align only in line with the crown and not at the position at which the calendar aperture is located in a crown at 3:45 dial.

With the day disk replaced with the donor from the 7S26, the day and date will now align with the SKX dial aperture.

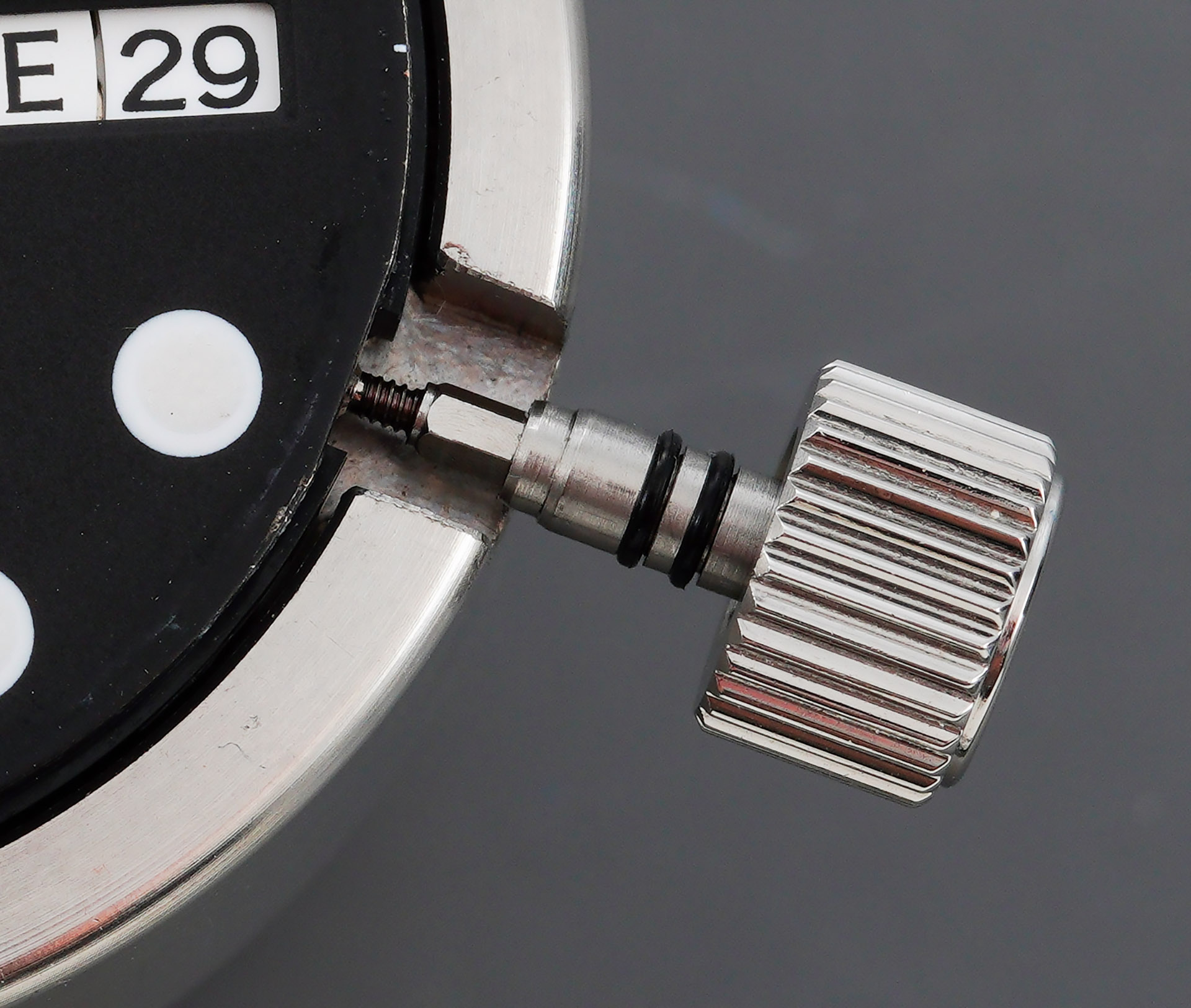

The final modification required by the movement substitution concerns the crown. The original is permanently crimped to the stem but the stem is incompatible with the NH36.

In the absence of an OEM replacement for a stand-alone crown, we need to turn to the aftermarket to source a separate crown compatible with the SKX case but which will accept a NH36 stem. The solution we have arrived at is shown in the photo below, the dial now having been fitted to the NH36.

This new crown employs three gaskets to the original’s one: two on the stem tube and one sitting at the back of the interior of the crown, behind the threads. In the photo above I have already trimmed the stem to size and applied thread-locker to the thread. With the hands fitted, we can now see the extent to which I have been able to clean up the edge of the dial.

The movement is now ready for the case but the case is not yet ready to receive the movement. A thorough clean has left it looking entirely none the worse for wear. A decision made by the owner to replace the original flat glass crystal with a double-domed sapphire, and we can go ahead and fit that, employing a brand new black nylon crystal gasket.

Given that this whole undertaking was initiated by the watch shipping water, a pressure test of the case, all three key points of entry now protected by fresh gasketry, seems appropriate. I do not have the equipment to test to the case’s rating of 20 bar but I can test up to about 7 bar and so that is what I did.

The case passed with flying colours and so we can move on to reuniting movement with case.

The first impression of the new look, for me at least, is that its owner has made the correct decision. The rather low profile, double-domed sapphire with its blue anti-reflective coating sets it off a treat.

The watch was originally purchased on a stainless steel jubilee bracelet. I am generally not a fan of bracelets but I am also not a fan of the original Z22 curved vent rubber strap, finding it stiff and uncomfortable. I must say though, having given this a spin on its jubilee, that I find myself revising my opinion about the benefit of a nice, loose, jangly bracelet with these somewhat large watches.

The jubilee transforms this from a conspicuous, ever-present high-profile lump to a comfortable everyday wearer.

In reviewing the result of this little project, I am reminded why this design is still in production, nearly 50 years after it first appeared in the form of the 150m 7548-7000 quartz diver’s watch in the late 1970s. It’s a classic piece of design. Thank you to Matt for agreeing to his watch being featured on the blog.

Really excellent work, photos and post! I have a pretty nice (never serviced) SKX009 from about 2008; and I’ve always wondered if the NH36 would be a drop-in replacement. You’ve certainly answered that question and more. I think I’ll show your post to my local watch repair shop and see if I can get them to hot rod mine in a similar fashion. If I’m successful I’ll put it up on Instagram and tag you.

Thank you! The proliferation of aftermarket parts certainly makes such an upgrade a great deal easier than might previously have been the case.

Hi Martin. I’d see this cockup as a fortuitous one indeed, since the two (and probably only) shortcoming of this iconic watch were addressed, namely the movement and crystal material. Cheers!

Yes, I agree. I was a bit unsure about the crystal initially but I think it’s definitely an improvement.

Great job. I’ve done this very same base upgrade on many a SKX in the past. It really is where the SKX007 should have evolved, rather than the push/pull crown of the newer Seiko 5’s. The owner should be able to get another few decades wear out of this watch thanks to your work.

I’m Currently wearing a very similar 30 year old 7002-7000 which I popped some fresh gaskets into last week. This ‘form following function’ design by Seiko will always be evergreen in my opinion.

It’s certainly demonstrated that it’s got legs. I’d not realised that the newer Seiko 5s don’t have screw down crowns. How odd.

Hi Martin,

Looking to replace my SKX007 crown gasket ahead of the summer. I have been trying to find the dimensions online, but I haven’t had any luck from reputable sources.

I know the part number is EZ0140B0A.

Some forums claim its

2.6mm (outer) x 1.5mm (inner) x1.0 (thickness)

I don’t see how this adds up? Maybe they are referring to the radius instead of diameter in the thickness measurement?

Could you share your expertise on the subject?

Kind regards,

Giuseppe

Apologies Giuseppe – I completely missed your comment but thanks for the reminder bump! I’m afraid the quick answer to your question is that I don’t know off the top of my head but the gasket code suggests that it is an E-profiled gasket (flat inner, rounded outer) of greater than 1.7mm total width and with an inner diameter of 1.40 mm. I note the extortionate cost of the replacement part -£8.15 + VAT + delivery for a gasket you could inhale without noticing. Good luck finding a suitable replacement.

All the best

Martin

Hi Martin, just following up on my SKX crown gasket query.

Regards,

Giuseppe

Apologies – please see my reply to your original message.