In 1963, Seiko’s luxury goods line-up spanned no fewer than seven sub-brands within a pricing structure in which the most expensive model was more than three times the price of the cheapest. At the zenith, the Grand Seiko 3180 chronometer at a hefty 25,000 Yen. At the base, the Seiko Crown Special, whose stainless-steel variant was priced at a rather more affordable 7,000 Yen. Interestingly, the Crown Special movement provides a great deal of the DNA for that aristocratic Grand Seiko, both being based on the Crown base calibre and in its Special incarnation, the Crown’s movement is not that far removed in its specification, if not overall level of refinement, from the 3180. Between these two bookends, we have, in decreasing order of status: the Seiko Liner Cronometer (20,000 Yen); the King Seiko 15034 (15,000 Yen in gold cap; 12,000 Yen in stainless steel); the Seiko Lord Marvel (12,800 Yen in gold cap); the Seiko Goldfeather (a watch whose charms have yet to exert any great influence over me); and finally, the subject of this current entry, the Seiko Cronos Special, one step up from the Crown Special.

The steel case variant of the Cronos Special was priced at 8,000 Yen. Its movement is a slightly detuned version of the one powering the King Seiko, whose price is a full 50% higher than the Cronos Special. In my book, that made the Cronos Special excellent value for money if the buyer in 1963 valued its tactile qualities, heft and the credentials of its movement rather more than the bragging rights of the King Seiko branding. Mind you, much the same could be said for the relative value offered by any of the incremental steps between Crown Special and Grand Seiko.

This rumination on pricing strategy, value and badge-engineering brings us neatly to our subject: a rather smart Seiko Cronos Special 15033 from June 1963. This particular watch was the last of four siblings to pass through my hands earlier this year, and by the time this one hove into view, a certain amount of muscle memory was being exercised, all four being powered by essentially the same movement.

In its appearance as well as in the hand, this certainly does not feel like a cut-price King Seiko, the impression of quality helped by the crisp lines of the case, the beautiful execution of the dial and the elegant hands.

The embossed crane symbol on the interior of the case back tells us that this watch was produced in the Daini Seikosha Kameido factory in Tokyo, as might have been expected given that the Cronos family line was conceived and designed by the Daini division.

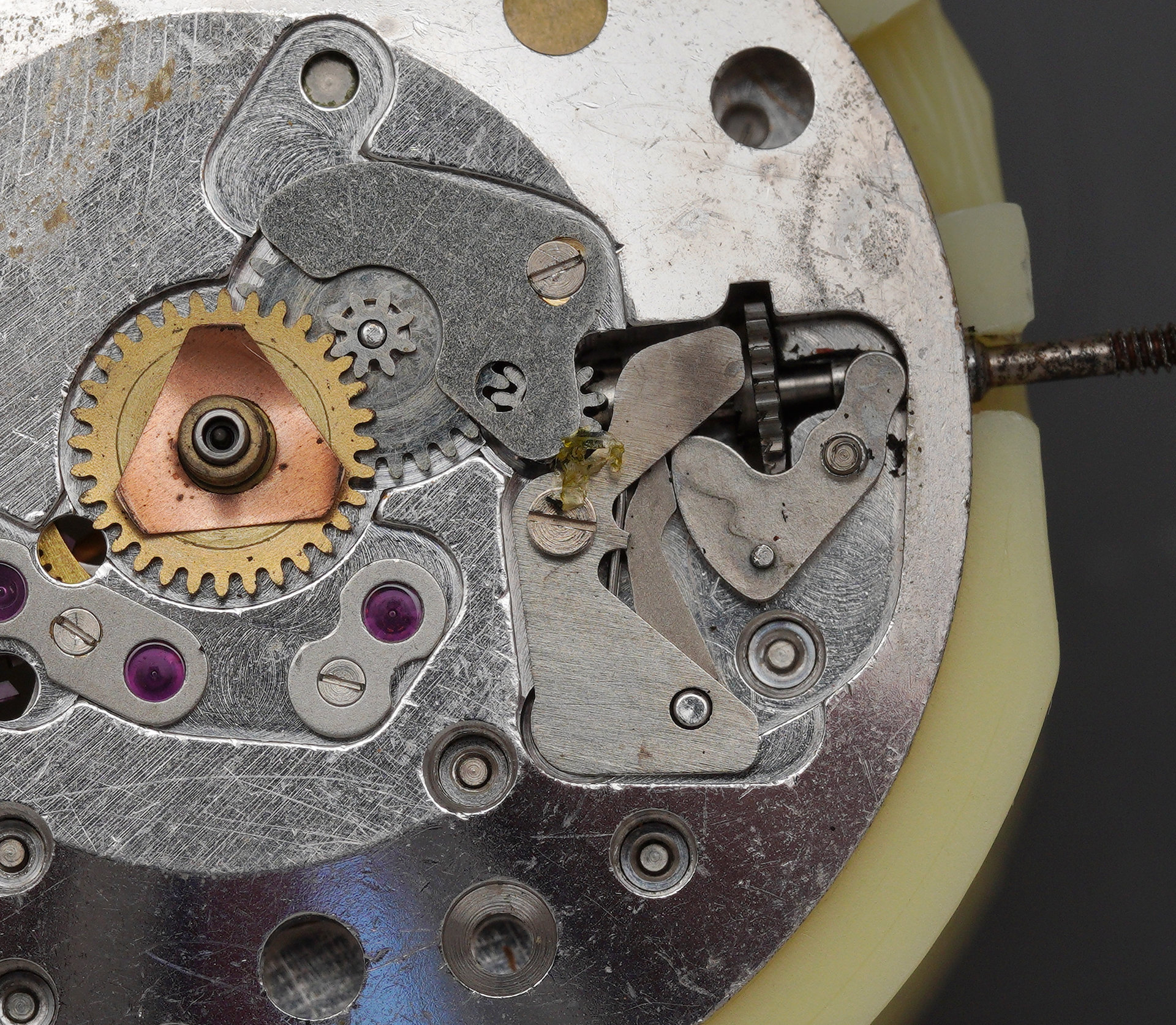

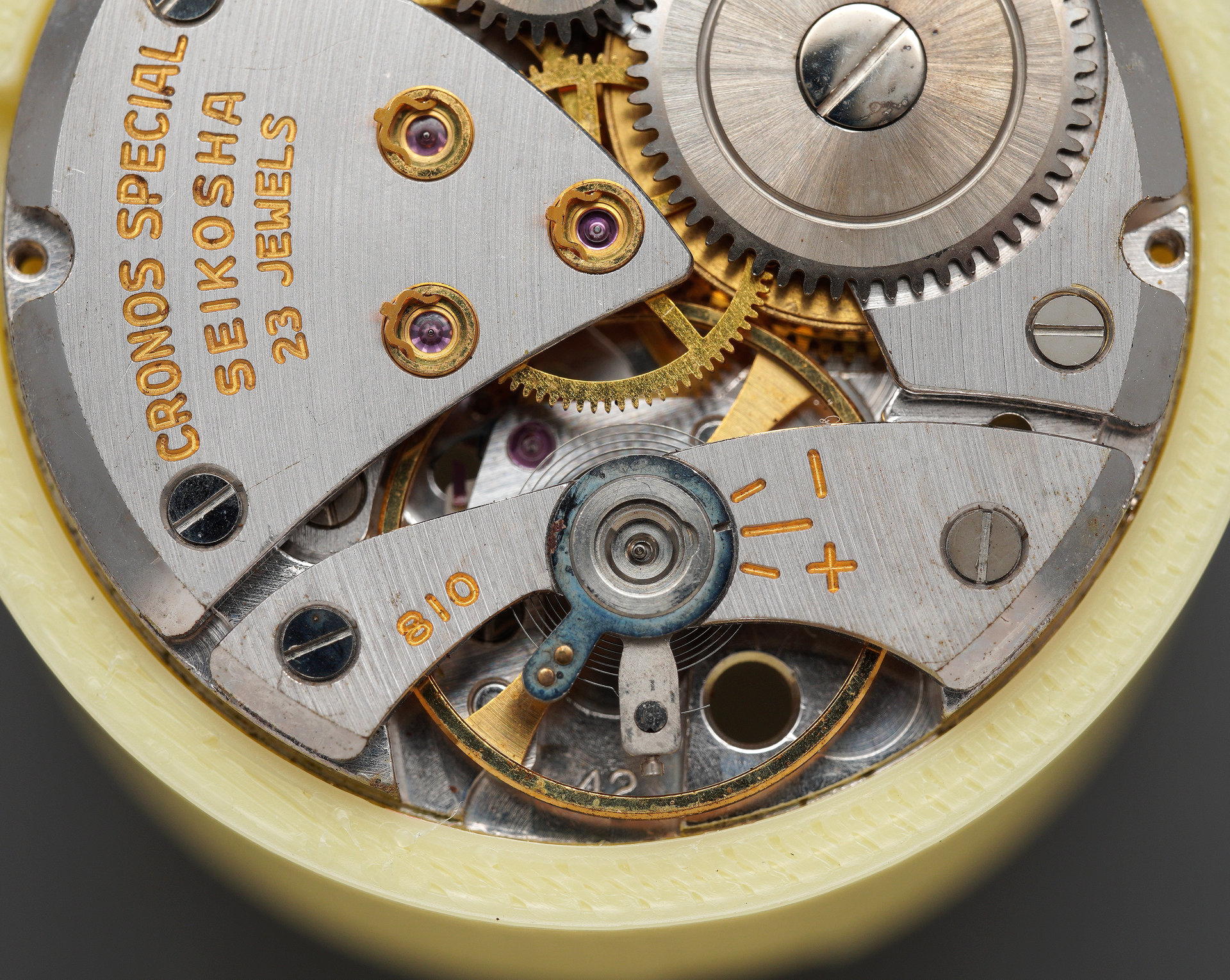

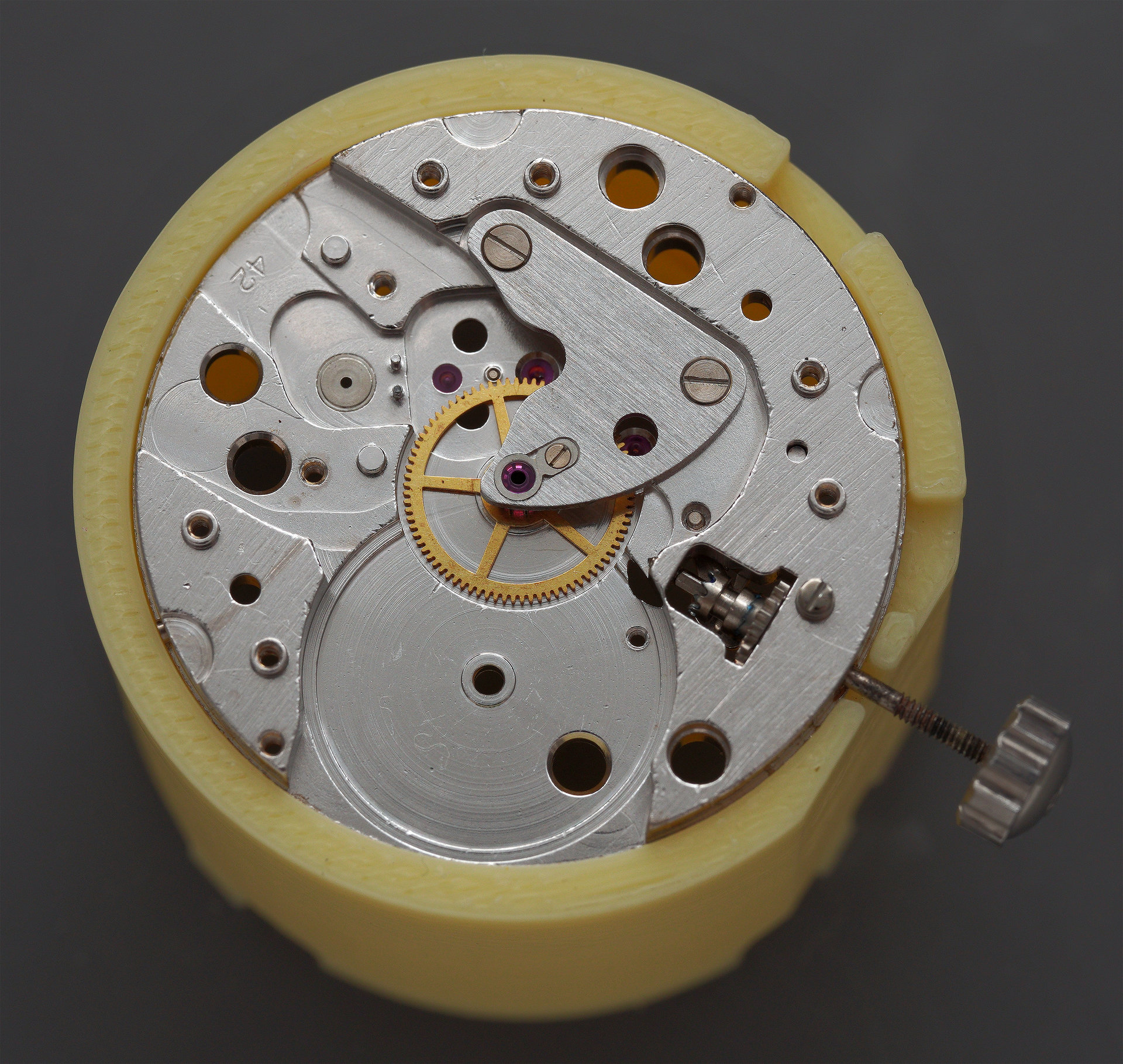

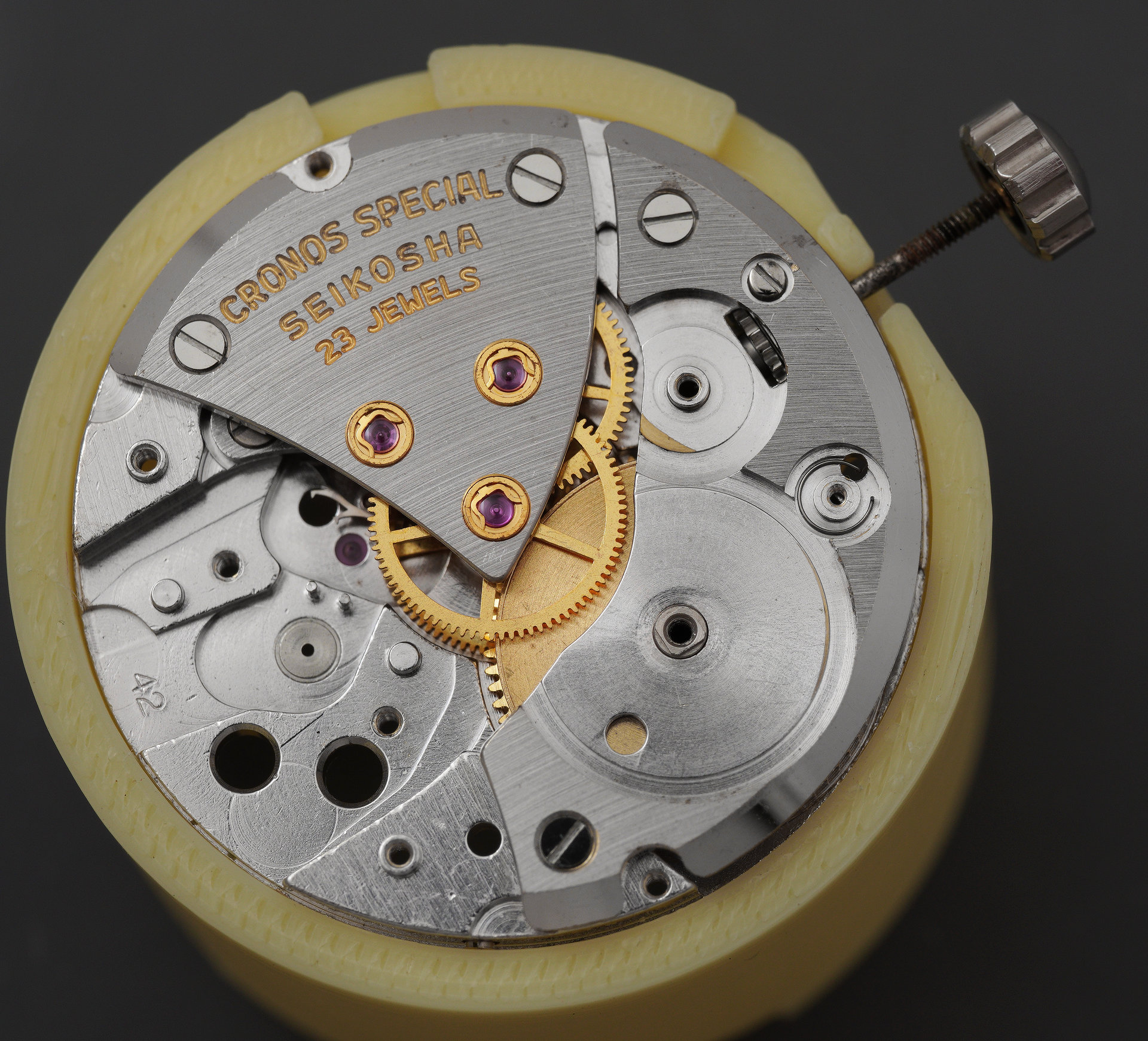

This initial view of the movement (below, left) is very suggestive of the familiar first generation King Seiko (below, right).

A comparison of the two highlights the differences though, the most obvious of which is the inscribed identification: Cronos Special Seikosha 23 Jewels in place of King Seiko 25 Jewels. Note also that the King Seiko has a movement serial number on the train bridge while the Cronos Special has its movement model number, 810, positioned on one arm of the balance bridge. Where the King Seiko has a teardrop fine adjuster fitted to the regulator, the Cronos does without. And finally (well, almost), the King Seiko has a rather more sumptuously-profiled ratchet wheel than that of the less flamboyant Cronos Special. Two other minor detail differences worth noting are the later-style click fitted to the Cronos (subsequently adopted by the King Seiko) and, curiously, a third securing screw fitted to the barrel bridge of the King Seiko, where the Cronos manages with just two.

I think it’s time to dig a little further into our subject by freeing the movement from its confines. This is achieved by removing the front bezel, complete with crystal.

The unobscured view that this provides of the dial confirms its generally fine condition but it also reveals minor water damage to the periphery, with some lifting of the lacquer along parts of the minute track.

Having extracted the crown and stem and the two casing screws, the movement lifts out from the top side of the case. Removing the dial and hands reveals a very common failure point on all Cronos and early King Seiko movements: the setting lever spring is broken.

Happily, the owner of this watch was aware of the failure in advance of sending it to me and had supplied a replacement part. An initial timing run on the timegrapher suggested that this movement was not at all happy: it was barely running at all, a condition seemingly corroborated by its generally very dirty condition but we will gain further insight into its reluctance to run in due course. I have documented the deconstruction of this family of movements on several occasions previously and so I propose just to pause once or twice in this account to highlight points of note. The first of these is the tarnished state of the balance bridge but in particular, the polished surface of the regulator.

Earlier, I noted that the jewel count on this movement is two shy of that of the King Seiko. Those two additional jewels in the latter can be found in the lid and base of the barrel. The Cronos Special does without.

The rest of the deconstruction proceeded without incident and revealed no additional significant issues (although watch this space).

Before subjecting the movement parts to the usual cleaning process, I dismantled and manually cleaned the patinated balance bridge.

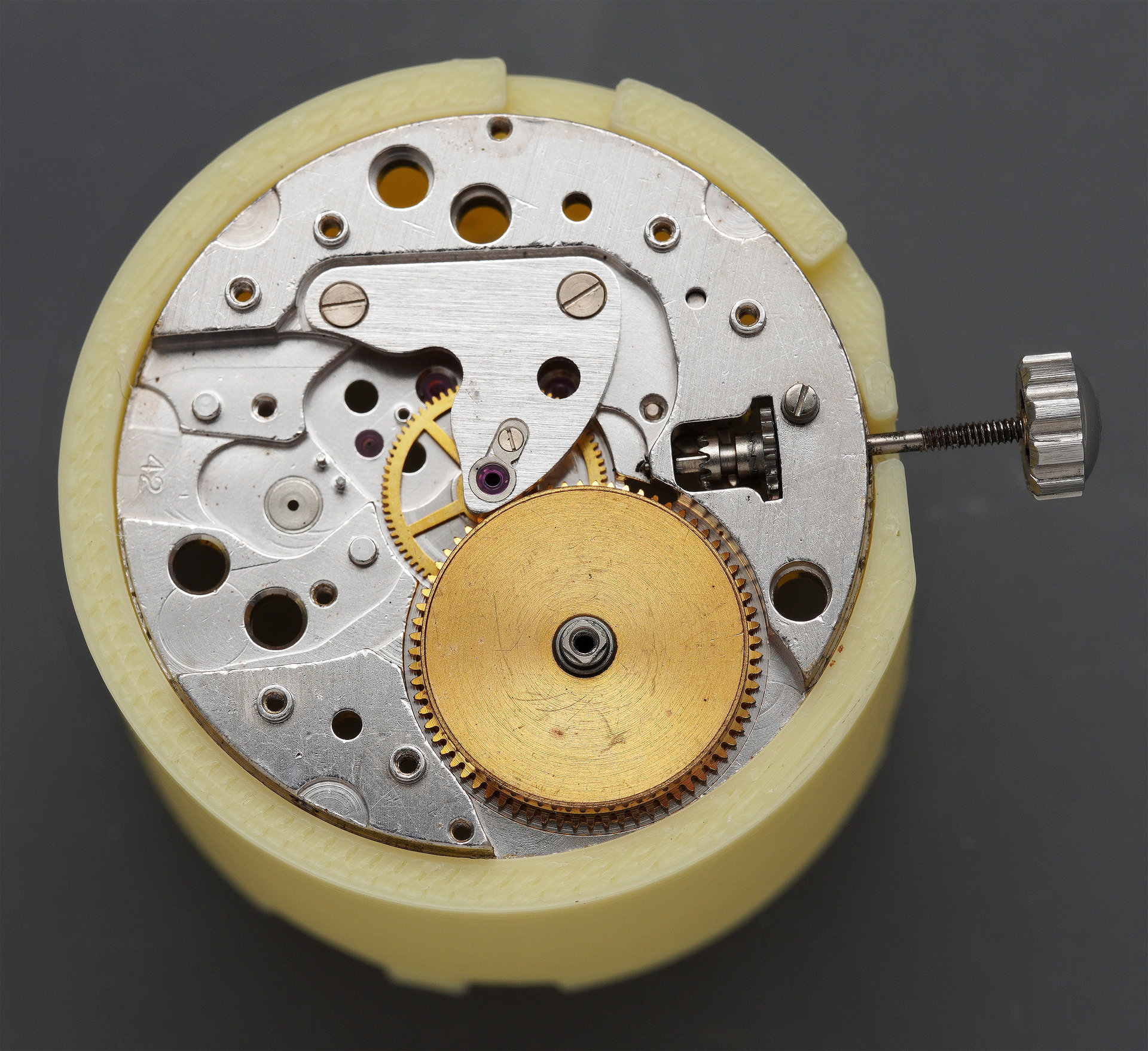

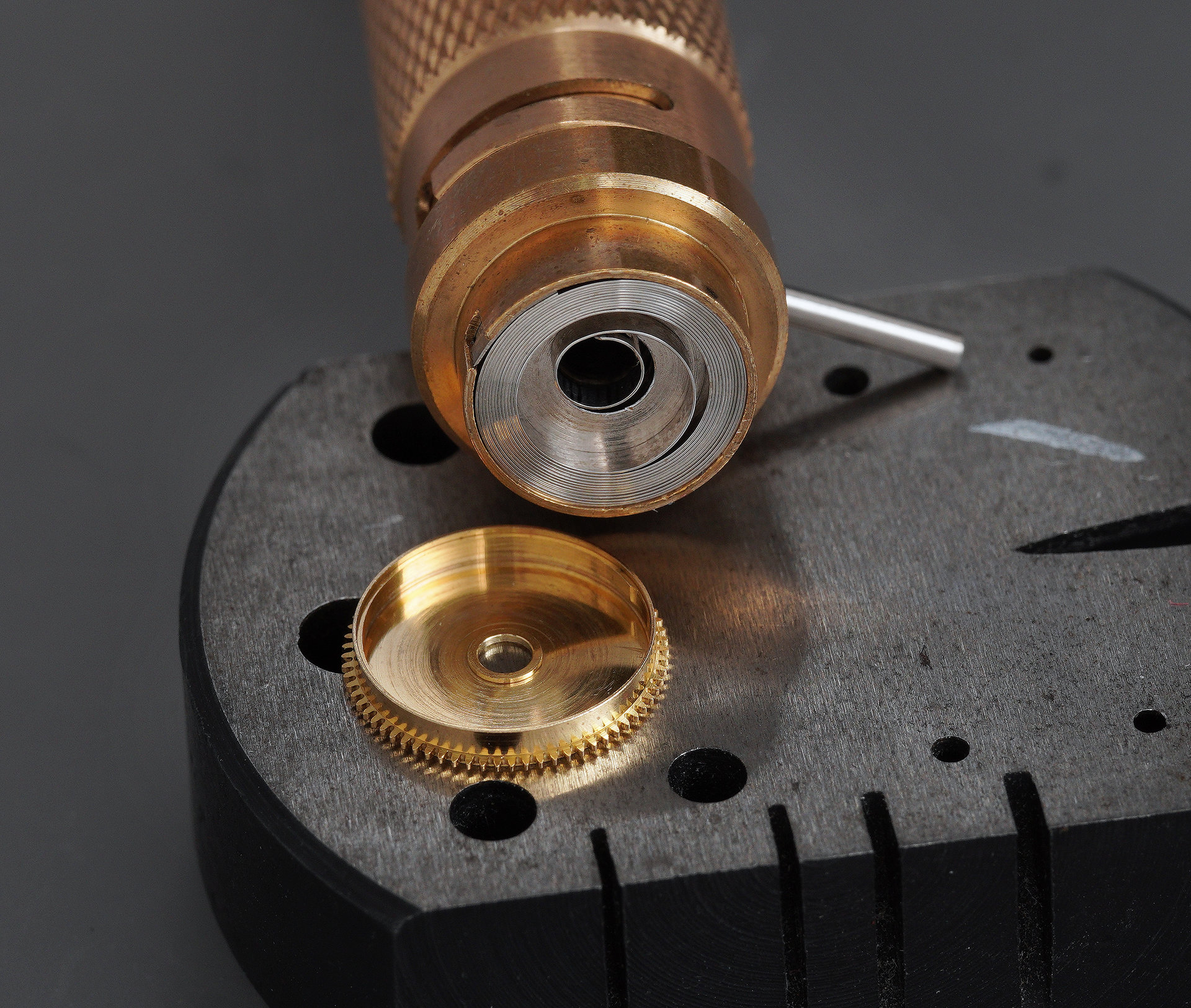

With the lengthy cleaning process complete, we can select reverse gear. My left arm slung figuratively over the passenger seat-back, and my head peering over my left shoulder (remember we drive on the correct side of the road in the UK), I navigate the initial stages of the reconstruction. We start by refitting the original mainspring to the cleaned barrel.

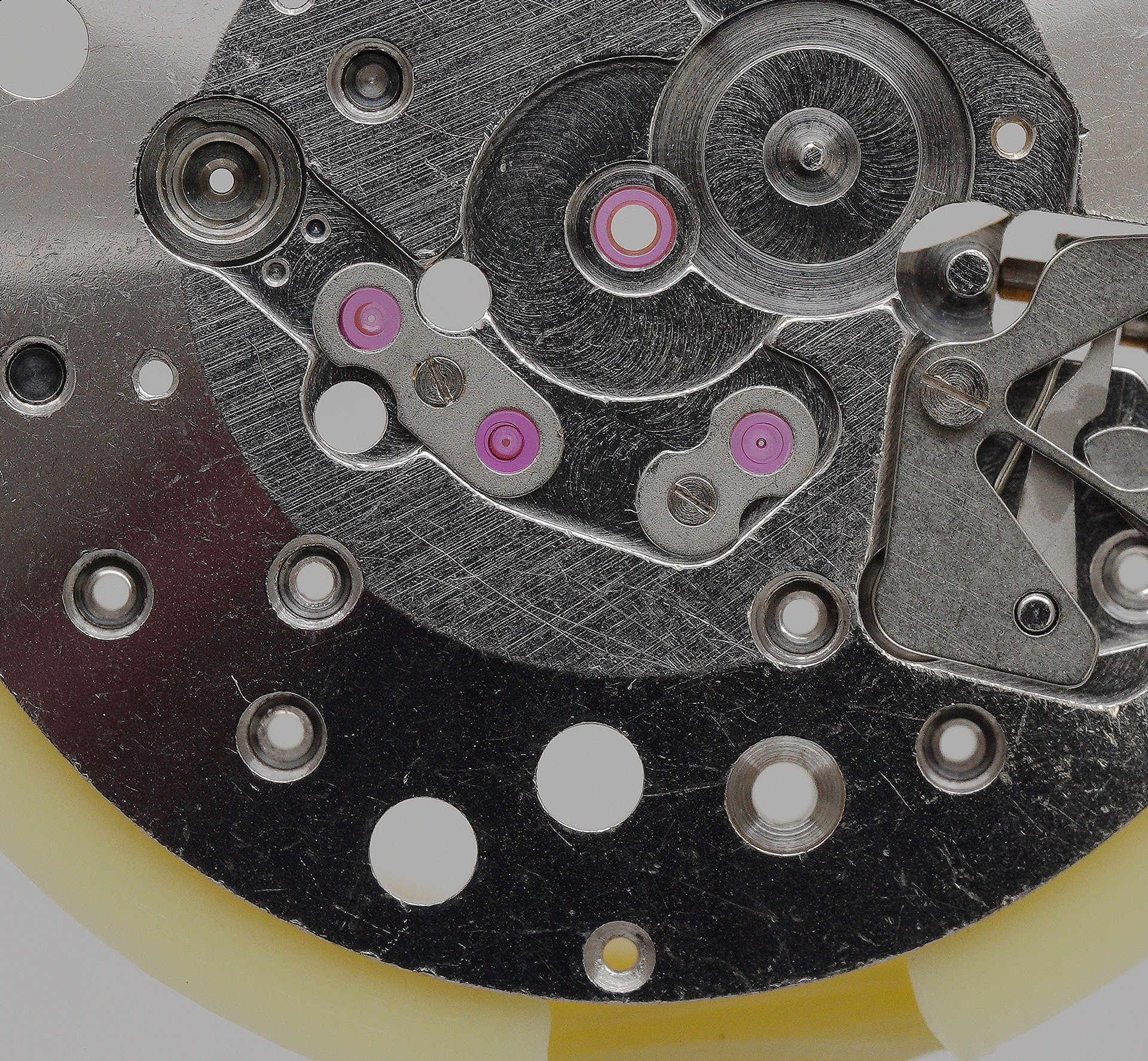

The two jewelled end-pieces for the pallet, escape wheel and third wheel are fitted with the latter two oiled.

Later incarnations of this family of movements would see these replaced with the familiar sprung Diafix cap jewels. On the subject of Diafix, there are three of these on the train bridge and these are refitted and lubricated next before moving on to fitting the setting parts, the centre wheel and its bridge.

The barrel and its bridge next find their way into position, at which point we can start to refit the going train. It was at this point that I hit a snag: when I loosely fitted the train bridge, the three train wheels (escape, third and sweep seconds) would not rotate freely when encouraged to do so by tickling the barrel. I went back and forth trying to see what might be causing the impediment and eventually identified the culprit as the tiny bearing plate that sits between the centre wheel and the sweep seconds wheel.

The plate was not sitting flush with the top of the centre wheel bridge, its front edge protruding ever so slightly (indicated above). This was enough to impede the rotation of the seconds wheel as the train bridge was tightened down. I suspect that the plate will have been bent out of shape during a previous intervention but the extent of the protrusion above the plane of the bridge could only really be discerned by observing it through a stereo microscope. The solution to the problem was to replace the plate with one harvested from a donor King Seiko movement.

The train wheels were now rotating freely and we can move on to the next steps in the rebuild.

The ratchet and crown wheels, as well as the click, have assumed a permanent rose gold tarnish, immune to the restorative powers of the watch cleaning fluid, but I think it lends the movement an appealing patina that marks its survival from its extended period of neglect.

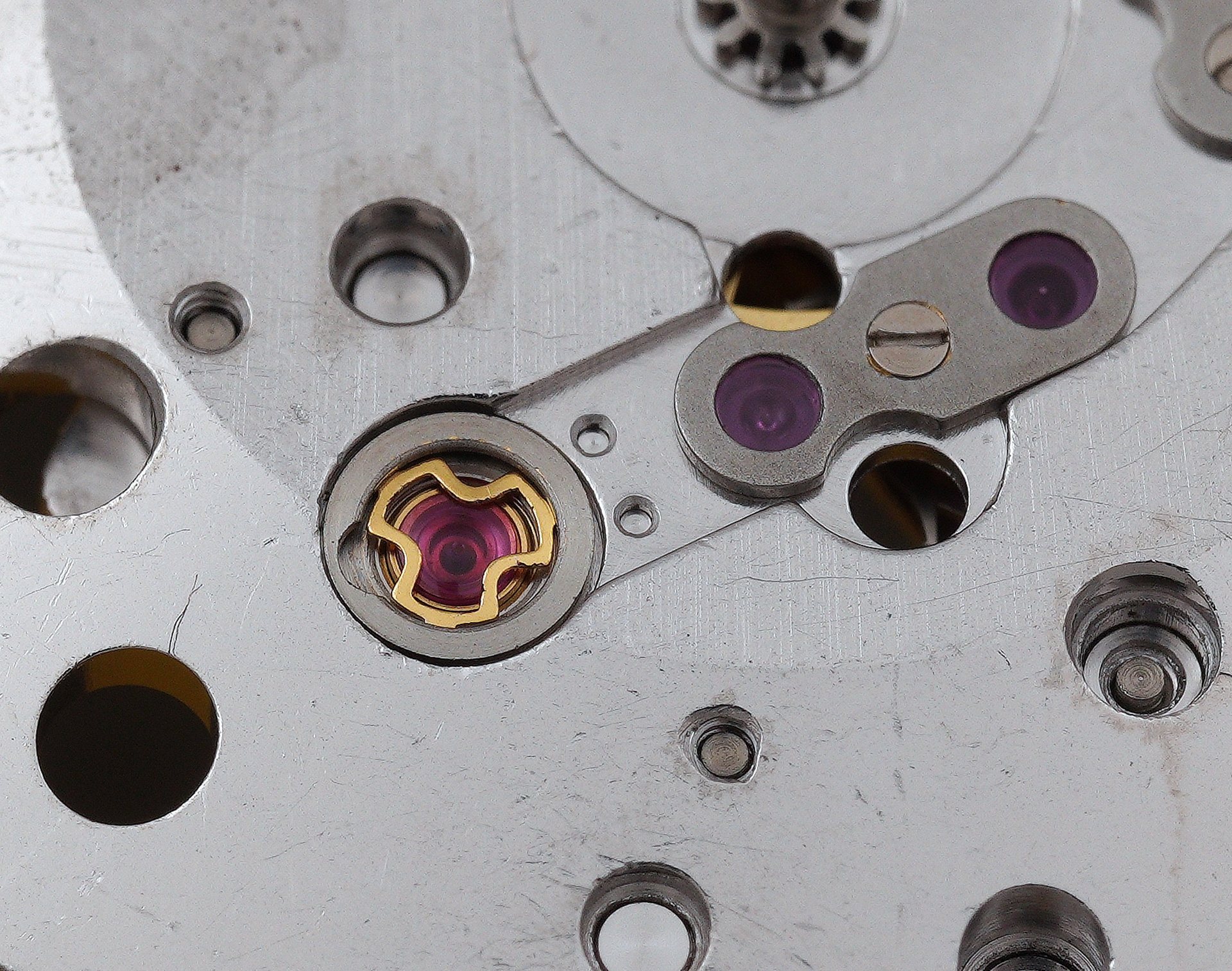

Two or three steps are required to take us from this point to a running movement. Having fitted the pallet fork and bridge, the Diashock setting on the dial side comes next.

A little power is wound into the mainspring, the balance eased into position, and once swinging away, capped with its Diashock.

The reassembly of the dial side components have included the fitting of the new replacement setting lever spring.

The dial and hands can be refitted at this point.

You may just be able to make out in the photo above, the beautiful spiral star-burst finish on the dial. Remove the crown and stem one last time, lower the movement into the case, secure it with its movement screws and refit the stem, at which point a fresh crystal is fitted to the bezel and the bezel pressed into place on the case.

With the dial and hands now protected, we can turn the watch onto its front and survey the completed movement, in its home environment, encircled by a fresh caseback gasket.

I think that this is a fitting point to close this entry, with this view of the lovely Cronos Special 810, a kissing cousin to the first King Seiko, but knocked down a peg in the interests of differentiation and the augmentation of an already slightly cluttered line-up of luxury Seiko models. Something for everyone perhaps?

Very interesting post, as always; and excellent work. Is it an illusion or do the hour markers exhibit a fair amount of variation? Comparing the 10 and the 1 seems to indicate 2 parallel grooves cut sometimes near the center of the marker and other times kind of skewed.

There may be an element of how the light is falling but there does seem to be some variation. Good spot!

I don’t have the time to work on my watches and after collecting all the parts for my grail, the 6015, I’m a bit sad that it sits neglected and unfinished but you’re why I keep it. You’re writing, photography, attention to detail is very soothing in this rather chaotic world. Thank you.

Thank you Gregor. I really appreciate it.

Does not the thinness of the Goldfeather excite you – even a little? I have a Skyliner – a relative porker compared to the Liner and the Goldfeather, but still impressively thin. It sits beautifully on the wrist – the thinness seems to make it wear bigger than it really is. I’d certainly not turn down a Goldfeather at a reasonable price! Damn – another model to watch out for…

Thanks for another fascinating blog. Not so much for feeding the addiction.

I would love to work on a Goldfeather movement but the watches themselves don’t do much for me. I have in fact been keeping an eye out for one that tickles my fancy a little. I expect that one will find its way to me, one way or another, at some point.

Hello Martin! I really enjoy seeing these Seikos from the 1960s. The spiral dial is quite beautiful and one I’ve not seen in later Seikos. Was this pattern indeed special, or have I just had my head in the proverbial sand. Also, wondering how the GS 3180 project is coming. Best Wishes in the new year!

Hi Tom,

I don’t know how special the spiral pattern was – I don’t think I’ve seen it before – but whether it was or not, it is certainly very beautiful. As for the Grand Seiko 3180, that is next on my list for my watch projects. The Lord Marvel was intended to be the appetiser, with the main course to come soon!

All the best

Martin