Tags

Seiko’s first wholly in-house automatic movement was the Gyro Marvel, developed in 1959 as an evolution of the Marvel/Laurel hand-wind movement. This was the first Seiko automatic to feature Seiko’s proprietary magic lever mechanism that enables bidirectional transmission of power from the rotation of the winding weight to the mainspring. The addition of the automatic winding module to the already quite tall Marvel (4.40 mm) resulted in a movement 6.55 mm thick and a watch that could not exactly be described as exactly sleek.

The Marvel/Laurel/Gyro Marvel line was a product of Suwa Seikosha whose factory was in Kamisuwa, in Nagano prefecture. Suwa Seikosha resolved to address the height issue affecting the Gyro Marvel by developing a self-winding series of watches whose thickness was not much different from traditional hand-wind watches.

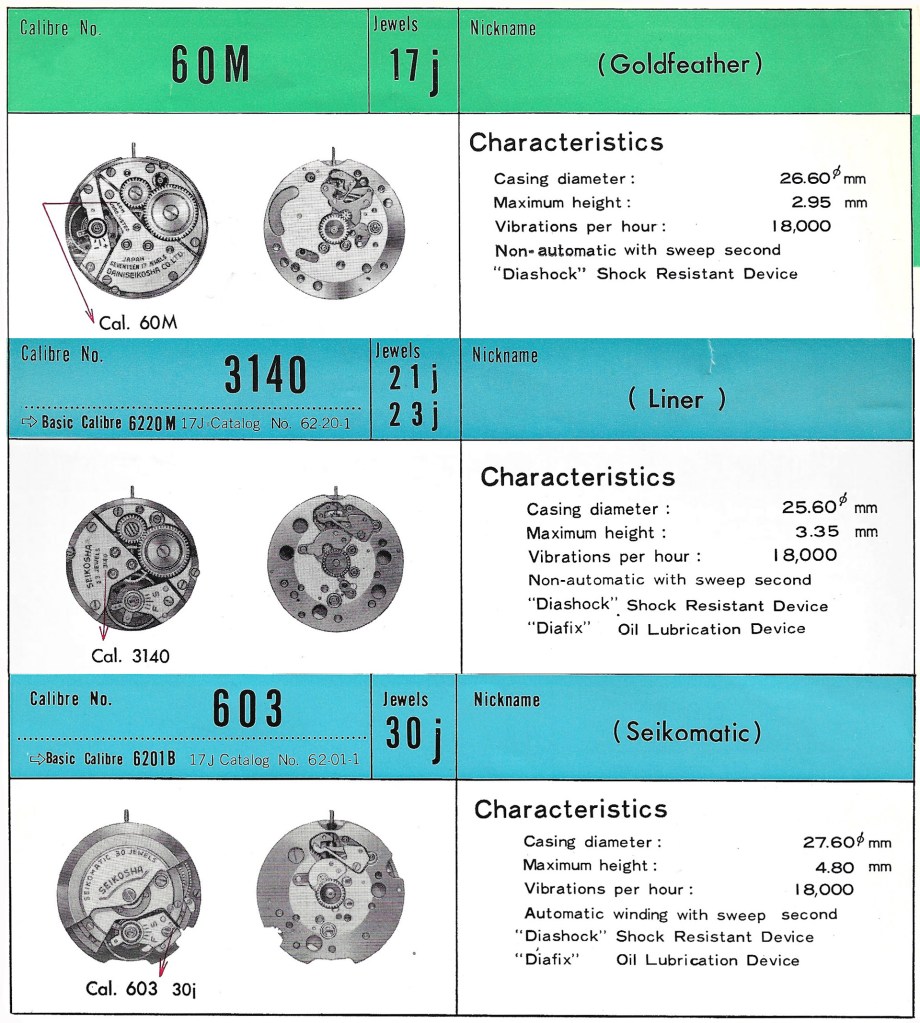

In accomplishing this objective, Suwa Seikosha had a choice of either adapting an existing hand-wind movement of considerably lesser height or designing a new movement from scratch. Seiko’s thinnest hand-wind movement at the time was the Goldfeather whose height of 2.95mm was a full 1.45mm thinner than the Marvel. However, the Goldfeather was a product of Seikosha Kameido, based at Seiko’s second factory in Kameido, Tokyo. At that time, there appeared to be a significant degree of inter-group rivalry that inhibited collaboration and consequently of consideration of that movement as the basis of a new, low-profile Suwa-developed automatic. With no other option available, Suwa undertook to develop a new movement that could form the basis of both hand-wind and automatic variants. Suwa claimed at the time that this was to be a completely new design, but the reality suggests that it drew very heavy inspiration from the Marvel and was effectively a slender evolution of that movement.

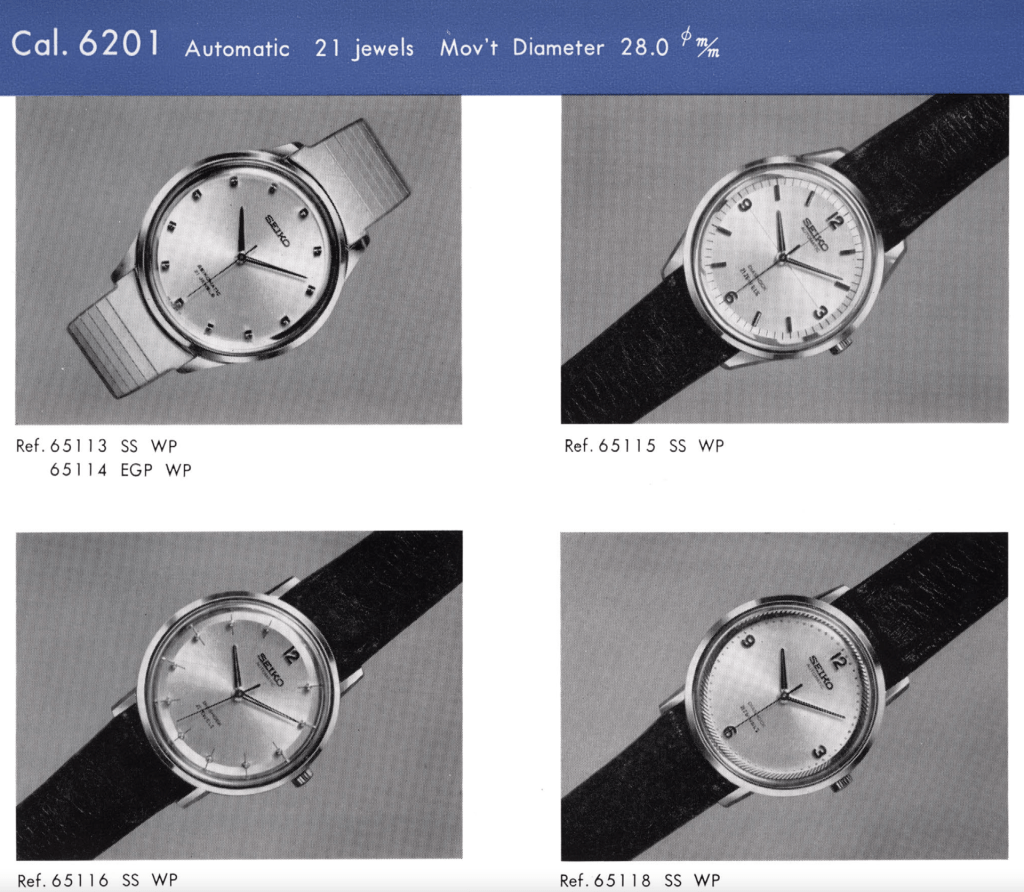

The result of this undertaking was the more or less parallel appearance of the Liner and Seikomatic series of movements, the Liner 3140 being the hand-wind variant and the Seikomatic 603, the automatic. In surveying the vital statistics listed in the extracts from the Seiko watch parts catalogues of the time, it is worth noting that at 4.80 mm height, the 603 automatic movement was only 0.4 mm thicker than the hand-wind Marvel/Laurel movement on which the Gyro Marvel was based. In that respect therefore, mission accomplished. In keeping with its low-profile dimensions, not only was the 603 not fitted with any hand-winding facility but the intention was for the crown to be tucked away at the 4 o’clock position and integrated into the lines of the case, all the better to avoid annoying entanglements with shirt sleeve cuffs.

The Seikomatic 603 was available in four versions with jewel counts of 17, 20, 21 and 30. The 20 jewel 603 was the first to be released with 17 and 30 jewel versions following. Although the watch parts catalogue lists a 21 jewel version, it was only fitted to export models and is essentially unobtainable in Japan. Even in overseas markets, it proves exceptionally elusive although perhaps slightly less so in later 6201 form. The 17, 20 and 21 jewel variants were rhodium plated, the more luxurious 30 jewel version, gold-plated.

As I have discussed on numerous occasions in the past, jewel-counts in this era of watch need to be viewed not only from the design perspective, where additional functional jewels can play a role in enhancing the performance of the watch, but also from the marketing perspective. In these early three-hander versions of the Seikomatic movement, there is far less opportunity for gratuitous jewel count inflation than in the later calendar-equipped versions of the Seikomatic (and subsequent Grand Seiko incarnations) but nevertheless, as we shall see, there is a sniff of what was to come in the 30 jewel 603. Perhaps though, we can revisit this question once we’ve revealed our case study for today’s entry: a Seikomatic 30 jewel 15031D, dating from January 1963. The watch mid-case is electro-gold-plated on a brass substrate to a thickness of 20 microns (EGP 20 microns) and the case back is gold-filled on stainless steel.

This photograph does not really do justice to just how tattily it presents in the flesh but what ought to be clear is that this is a watch with more than its fair share of patina: the gold-plating on the case is very well preserved, although quite badly tarnished; the watch dial is not only significantly tarnished but also very dirty owing to the gaping hole in the side of the cracked acrylic crystal.

The hour and minute hands are making contact with the dial, and the seconds hand is badly damaged and probably beyond saving.

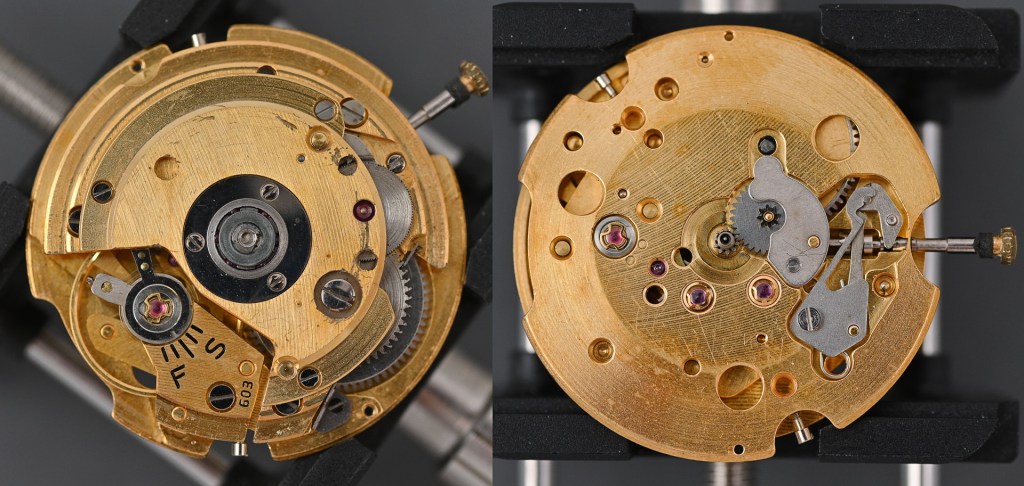

The movement, on the other hand, looks to be in fine cosmetic fettle.

I always find the movement extraction process to be slightly awkward with these old-fashioned three-piece cases. The movement is extracted from the dial side once the bezel and crystal have been removed because the movement is effectively suspended within the mid-case, supported by the dial. It is further secured by a pair of case screws, accesed from the case back side (one of which is missing, as indicated below).

The setting lever axle is of the screw type rather than the push-type used in later 62 series Seikomatic movements. Once the crown and stem have been released, and the case screw removed, the movement can be lifted out from the dial side.

Removing the dial requires the two dial screws to be loosened and at this point we can survey the naked movement, the hour wheel and its washer having been set to one side.

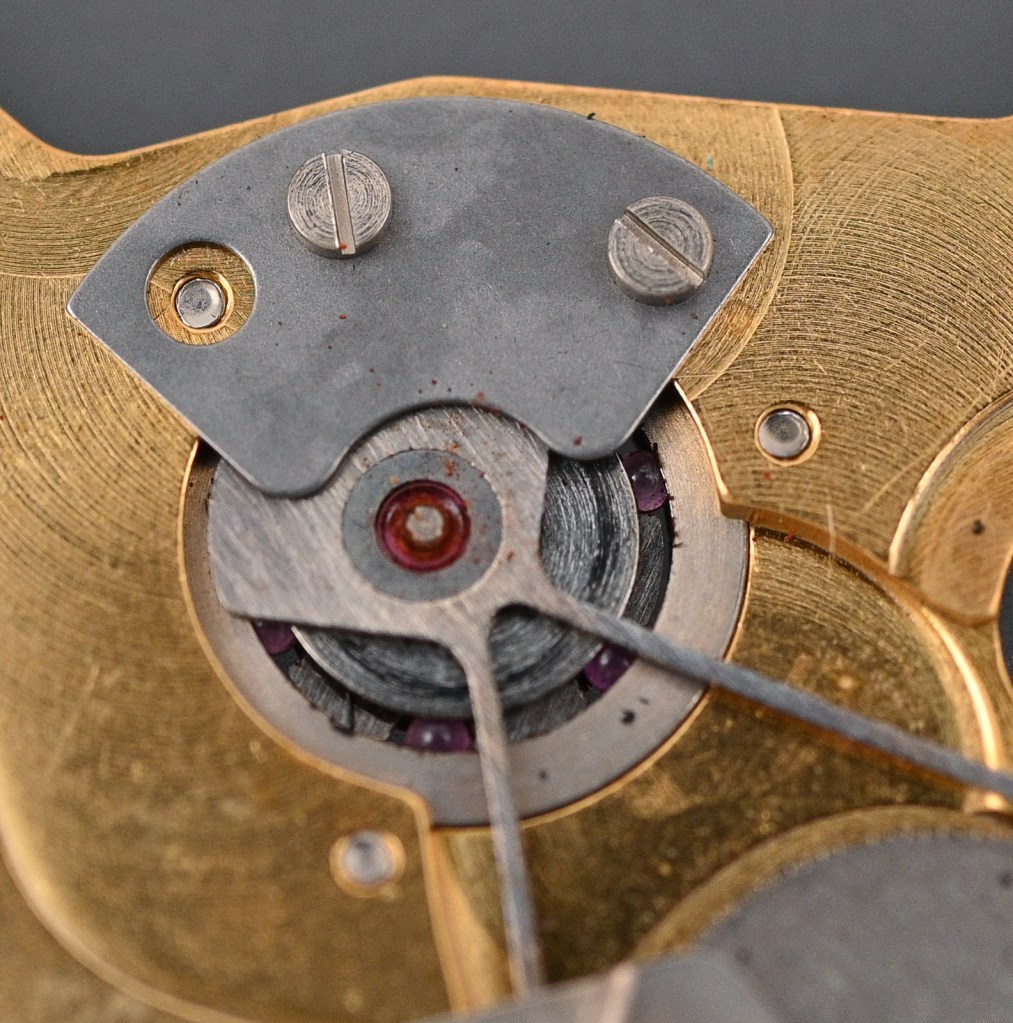

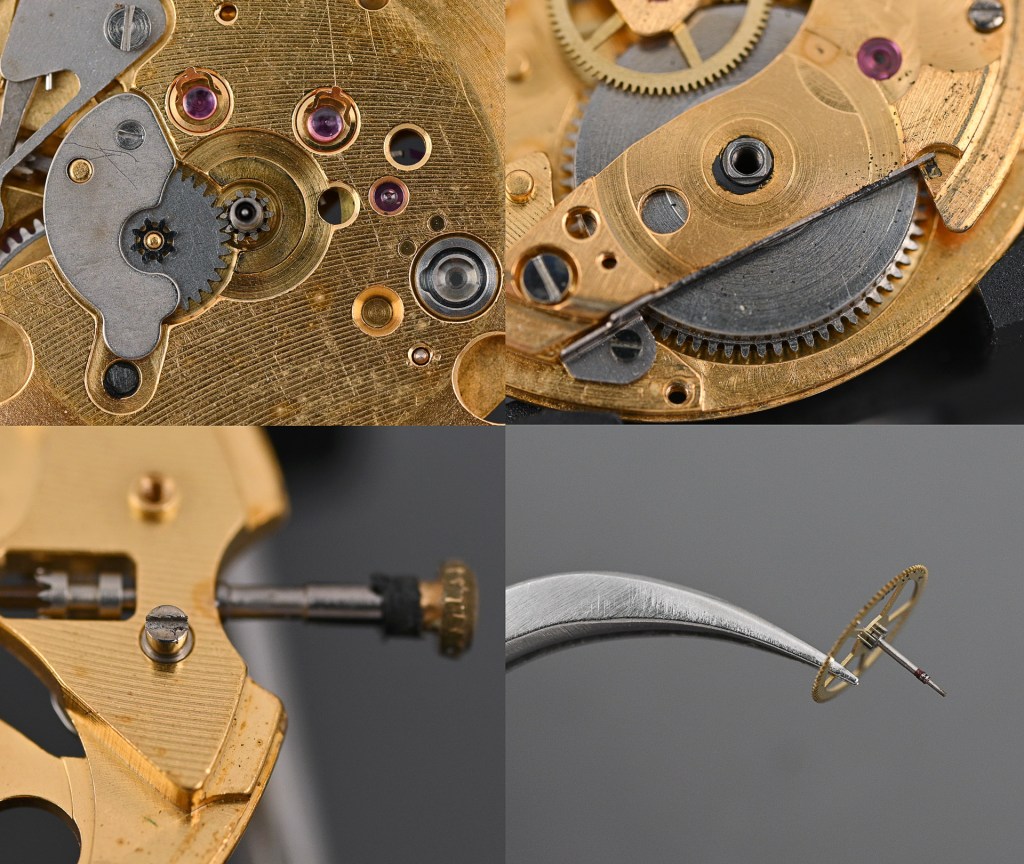

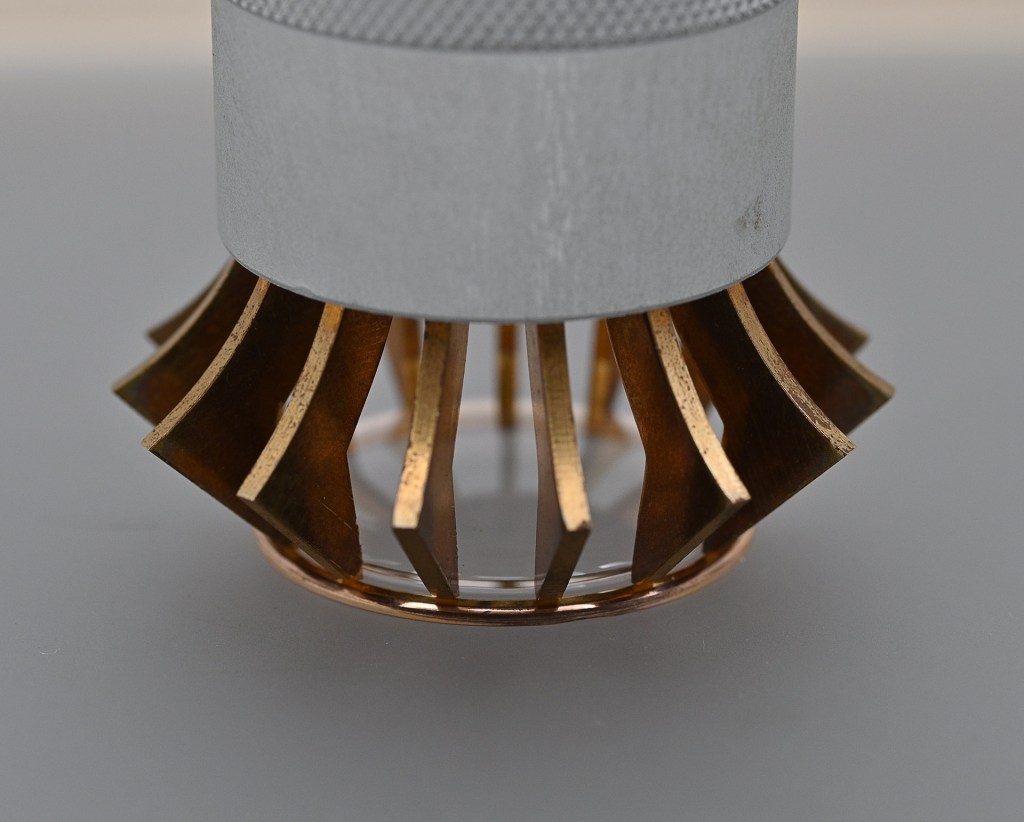

The only real cosmetic damage to the movement is to the automatic winding bridge but otherwise it all looks rather beautiful. Before moving further, it is probably worth coming to a judgement about the advertised jewel count. The 20 jewel 603 that we have met previously is essentially a 17 jewel base movement augmented by three jewels serving the autowinding module. All of the 20 jewels therefore serve a clear purpose, and the only cap jewels present are those that top and tail the Diashock settings. In the 30 jewel variant we have here, you will see from the photo above that the escape and third wheel benefit from Diafix settings on the dial side and these are duplicated on the train side. The four Diafix settings therefore add a further four jewels over the 20 jewel 603, taking the tally to 24. So where do the remaining 6 jewels lie? Well, if you squint at the autowinding bridge, you may notice that the bearings are not made from steel, as is usually the case, but from ruby. The silky rotation of the winding weight in this movement owes no small part to the presence of those six ruby spheres: 20 + 4 + 6 = 30.

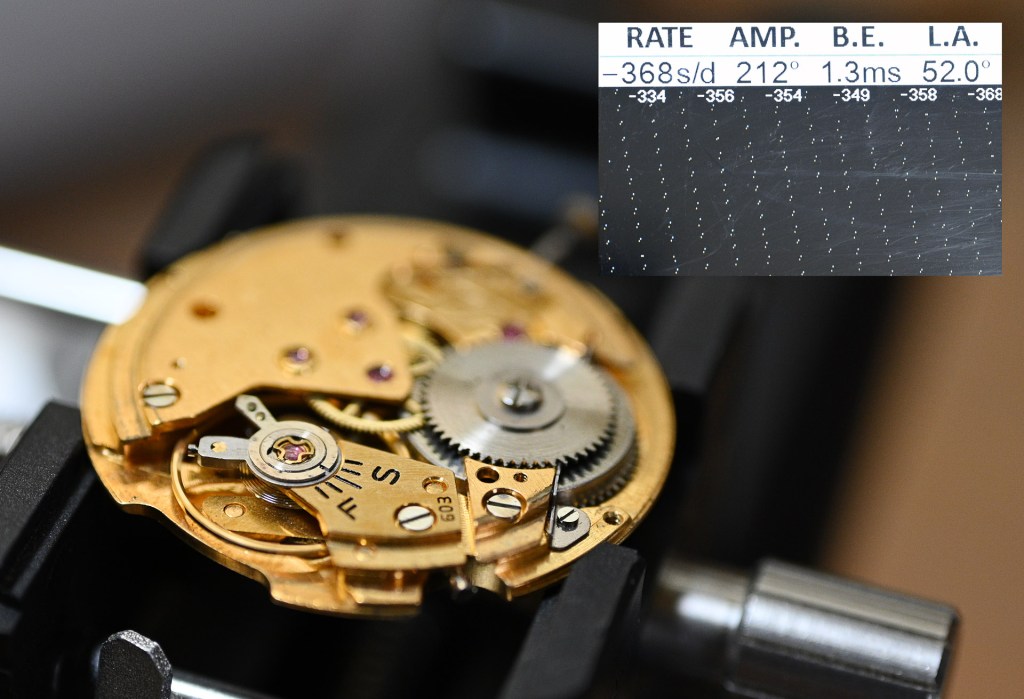

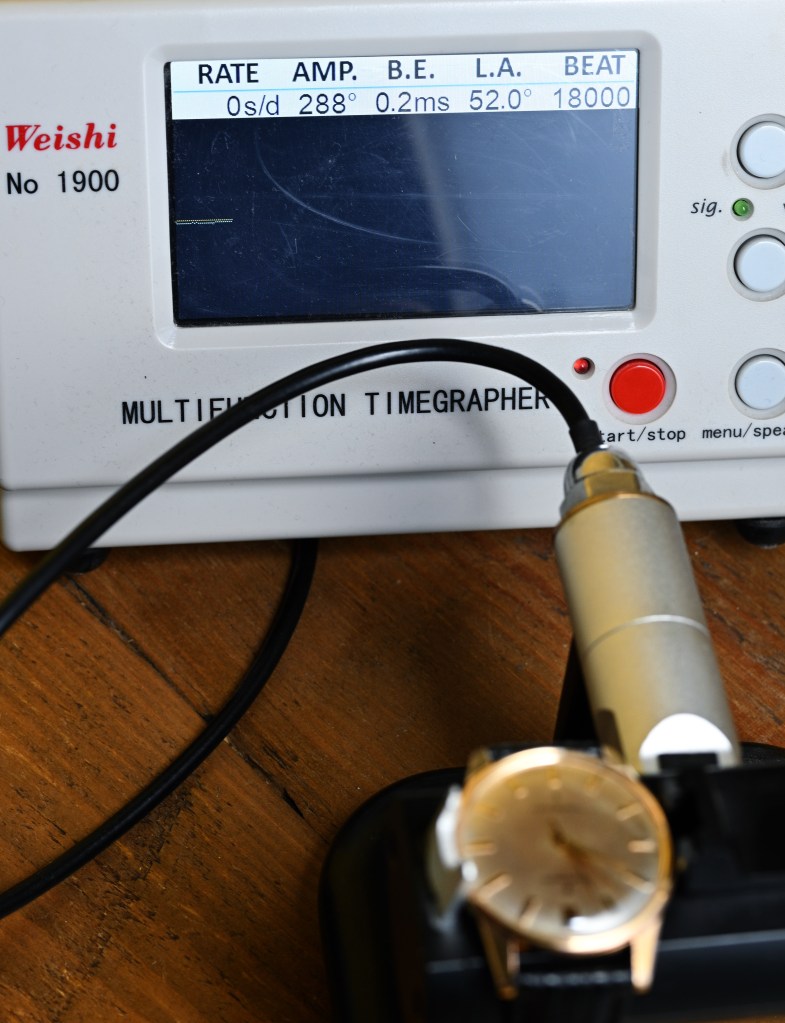

Before continuing to dismantle the movement, it is time to get an idea of how well it is running, pre-service. With the autowinding module removed, I wound in a full wind of power and put the movement on the watch timing machine.

Pretty chronic is the answer. The amplitude is rather poor, the beat error is very high, and the rate is very slow. Plenty of room for improvement. The journey to achieving that starts with the deconstruction of the movement into its constituent parts. We have followed this process with this family of movements on numerous occasions in the past (examples of which can be found here and here) and so I shall make just four observations in documenting the process here: the dial side of this movement is nicely decorated, with large radius curved grooves along the flat top of the main plate and radial brushing on the surrounding bevelled slope. All the better to show off those two Diafix orbs, peering out, their eye-lashes all a flutter; the barrel has leaked some of its molybdenum grease into the barrel arbor hole in the barrel and train wheel bridge; the seconds wheel pinion is caked in solidified moebius A watch oil; and the setting axle screw head has seen some abuse.

The last order of business in the disassembly is to unfurl the mainspring and assess its health. All looks fine and dandy.

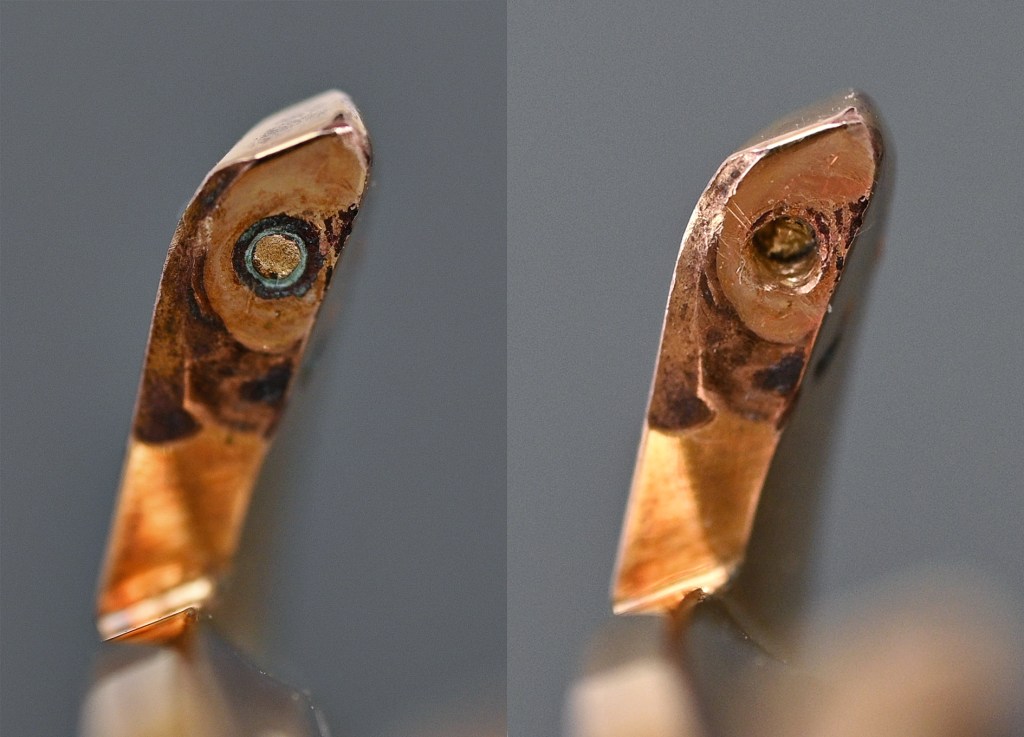

While the movement parts are cleaning, let’s turn our attention to the case. My normal expectation of gold-plated cases of this age is that they are rarely if ever salvageable, skin acids normally having etched away large swathes of the plating down to the ugly brass below. In this case, however, the case has a lovely rose-coloured patina and the friction wear that exists has, by and large, not extended completely through the plating. The assessment, therefore, is that this is a case worth spending a little time on.

However, there was one small fly in the ointment. One of the spring bar tips had broken off in the lower right lug and was stuck fast. I considered briefly the possibility of using alum solution to dissolve the steel tip but I didn’t want to risk damaging the plating. The solution was to use a selection of fine drill bits fitted to my Archimedes hand drill. The result of this operation was not especially pretty, but it was certainly effective and the lug hole is now fit for purpose.

The rest of the case required some spirited work with pegwood, toothpaste and an old toothbrush, the result of which a conversion of the dull rosy patina to a lovely reddish-gold shine.

The movement reconstruction begins, as usual, with the refitting of the mainspring to the barrel and the fitting and oiling of the Diafix settings, in this case numbering four.

Initial mainplate assembly follow a route from setting parts via centre wheel to cannon pinion and minute wheel.

The stage is set for the assembly of the gear train, topped off with the barrel and train wheel bridge. In fitting the latter, I note that it is not completely flat, there being a slight upwards curve along a line crossing the barrel.

This is not really a cause for concern because it is rectified simply by fastening down the bridge. With the escapement complete and oiled and the dial-side Diashock fitted, we can fit the balance, wind in some power and we have a running movement.

An initial timing measurement revealed that the movement was magnetised and following demagnetisation, I was able to get very respectable numbers from a preliminary regulation. More on that later.

The next job is to fit the dial and then to locate the watch on a stable platform to fit the hands. The case provides as good a base as any.

At this stage the movement is unsecured in the case and so the next task is to fit a crystal to the bezel and then the crystal and bezel to the case. The aperture in the bezel is 33.8 mm diameter and so I select a 34 mm crystal and set about compressing it before fitting to the bezel.

The bezel has a cut-out on its flat underside to accommodate the crown and so this must be aligned first before pressing the bezel into position.

The crystal has a pleasing profile, ne? Once the bezel assembly has been pressed into position, the case can be inverted and the two movement screws fitted to properly secure the movement to the mid-case. Then follows the reassembled autowinding mechanism and finally the winding weight.

Before sealing the deal, we need to undertake a final regulation. The watch was running a little fast at this point, having been through a couple of wind up/wind down cycles and so I adjusted the timing to flatten out the rate to an even 0.0 seconds per day, dial up.

The measurements at the two other positions were as follows:

Crown down: –5 s/d, 250° amplitude, 0.1 ms beat error

Dial down: 0 s/d, 263° amplitude, 0.0 ms beat error

The watch may run a little slow with this adjustment but I am astonished at how well it is performing, given that this watch is very nearly 60 years old and that none of the functional movement parts have been replaced. The only parts I exchanged were for cosmetic reasons: the autowinding bridge, the ratchet wheel and the setting lever axle.

The caseback is aligned with its cutout between the two lower lugs and then pressed back into place using some determined finger pressure.

Finally, a pair of fresh 19mm spring bars and a suitable black leather strap seals the deal.

I originally embarked on this project as a stop gap while I negotiate some local perturbations to my environment (a building project encompassing a new workshop) but much to my surprise, the result is something that greatly exceeds my expectation. This is a very beautiful watch, enhanced by its patina, and which is running as well as any 60 year old Seikomatic has a right to.

I have enjoyed this one also because it has acted as a prompt to educate myself better about the origins of the Seikomatic sub-brand. I absolutely love these watches and am glad that they remain relatively under-appreciated among collectors and speculators. Let’s keep it that way. Mum’s the word.

Acknowledgement: I must recognise the excellent Japanese Seikomatic site http://matic6246.web.fc2.com/index.html as a source of much useful intelligence on the history of the Seikomatic brand, as well as technical information about the movements. Very well worth a browse via Google Translate.

Rose gold patination , a dial of the most elegant simplicity and a tale well told of a sympathetic and thorough restoration. Chapeau…

Thank you!

Stunning work on a stunning watch.

Thank you!

Hi

I have one who need a little TLC and I would be glad to have the ref of the glass you have used !!!

Your watch is so amazing !!!!

Best regards

Xavier

Thank you! The crystal was either a low domed BCL 34.0mm or a Sternkreuz N 34.0. I hope that helps.

Love to know if that was a replacement seconds hand (if so, nice match), or if you straightened it out.

It was a replacement. I have a bunch of gold-plated hands from scrap Crowns, Cronos, and Marvels and had one seconds hand that was a perfect match.

Love the patina, good job.

Thanks!