Tags

In the eyes of a typical consumer on the hunt for a new wristwatch, the received wisdom is that a Seiko represents the quality mainstream yet affordable choice but if you seek something a little more exclusive or luxurious, something that signals your elevated status in life, then more likely than not, a Rolex will be the default choice. The notion of a Seiko as a high end timepiece challenges all established heirarchical conventions and if you were misguided enough to suggest such on any one of a number of watch forums, you are likely to initiate fierce discussion extending to dozens of posts ranging from level-headed to naked and irrational fanboyism (from both camps). I’ve occasionally allowed myself to be drawn into such debates but by and large stay out if it because the views on each side are so entrenched that to contribute serves no purpose other than to raise one’s blood pressure.

The reason for such conflicting opinion derives not so much from the perception of Seiko as a mainstream brand with its huge customer base, but from skepticism about the value proposition of the much more aspirational Grand Seiko sub-brand; a sub-brand that, in contrast to its parent, offers a level of exclusivity that Rolex owners can only dream of. The question that remains then is whether that exclusivity is delivered in a watch whose quality can compete with the more obvious upmarket charms of a Rolex. Why all the focus on Rolex rather than any one of numerous other Swiss brands? Well I suppose because it is the obvious choice, Rolex being by far and away the most well-known of the prestige brands but also because in spite of the usual association of up-market positioning with exclusivity, a Rolex is actually a mass-produced watch with production numbers in the millions. The compulsion to make the comparison then derives from the rather interesting contrast to be drawn between a hand made, high quality watch produced in small numbers yet priced at a point that competes on paper with a mass-produced watch from a very much more obviously up-market brand.

Until very recently, I’ve not really been in a position to offer an objective view on the matter. A few years ago on a trip to Japan, I wondered into a watch show in one of the posher department stores in Tokyo and was able to handle models from both brands. I have to say I was completely blown away with the tactile quality of the GS watches yet was left with an impression of the Rolexes I handled of very solid, supremely well made watches but not what I’d describe as luxurious. That experience certainly made an impression and clouded my view on the merits of the two brands until such time as I found myself owning examples of each.

One of the problems for GS as a brand is that, although it can trace its roots back to 1960, for much of its history, Grand Seiko was available only on the Japanese domestic market and to the outside world was largely unknown. In the modern watch market, this perceived lack of heritage tends to lead folk into playing the Lexus card when classifying Grand Seiko as a brand worthy of consideration at the same price point as mid-tier Rolexes.

In making a comparison of models drawn from each brand, I am limited of course by what I have available and so while the selection would appear to make itself, the choice is not at all arbitrary. I am writing this post precisely because it has occurred to me that on paper the two have much in common: both are vintage watches from the same era; both are 36 mm in diameter; both fitted with raised acrylic crystals; both feature low-beat automatic chronometer movements. So let us introduce the contenders: in the red corner, the establishment figure, a pukka classic, the Rolex DateJust 1603. In the blue corner, that upstart pretender from the land of the rising sun, the Grand Seiko 62GS.

The DateJust was first introduced in 1945 but, in spite of the countless iterations and refinements over the years, the classic oyster case design survived more or less intact until about 2012 with the appearance of the rather more blingy and to my eyes much less elegant 116200 family of 36 mm DJ’s.

The DateJust was first introduced in 1945 but, in spite of the countless iterations and refinements over the years, the classic oyster case design survived more or less intact until about 2012 with the appearance of the rather more blingy and to my eyes much less elegant 116200 family of 36 mm DJ’s.

The 62GS we covered in some detail in the previous post and in the heritage stakes it can’t hold a candle to the Rolex. However, it does occupy a place of some significance in being the first automatic Grand Seiko and although it was only produced for three short years from 1965 to 1968, it was revived in 2015 as part of the Seiko 55th Anniversary celebrations in the SBGR09x series and so in some sense it survives to the present day.

My DateJust 1603 dates from 1974 and so is 6 years younger than my GS 6245-9001 but its design and specification remained unchanged from those produced in the same year as the GS. To all intents and purposes then, the two watches are contemporaries although they will only have fought it out in that capacity in the Japanese domestic market of the time.

I thought in making the comparison, I’d assess the two watches in a two categories, inner and outer: the former requiring me to be as objective as I can but with the latter my subjectivity will hold sway. Let’s start out shallow and assess the looks first:

Exterior

The Rolex is without doubt a beautiful watch with real presence. However, when I received it, I confess to feeling slightly underwhelmed. The box crystal had lost its crisp edges with wear, the cyclops was scratched and the jubilee bracelet looked tired and old-fashioned. In fact, on the jubilee, it felt just a little bit like an old man’s watch.

The dial and hands though are properly gorgeous and even in its pre-fettle state, the whole watch had an undeniable feel of quality about it. My reservations were not strong enough though to divert me from lavishing upon it a proper service at a Rolex approved independent and that turned out to be absolutely the correct decision. The watch returned with its bracelet reconditioned, the case lightly refinished and fitted with a new crown tube and acrylic crystal and with the movement fit as a fiddle. I am still not that keen on the bracelet though and so, somewhat counter to convention, thought I’d give it a try on a NATO.

The dial and hands though are properly gorgeous and even in its pre-fettle state, the whole watch had an undeniable feel of quality about it. My reservations were not strong enough though to divert me from lavishing upon it a proper service at a Rolex approved independent and that turned out to be absolutely the correct decision. The watch returned with its bracelet reconditioned, the case lightly refinished and fitted with a new crown tube and acrylic crystal and with the movement fit as a fiddle. I am still not that keen on the bracelet though and so, somewhat counter to convention, thought I’d give it a try on a NATO.

Somehow, so equipped, the air of fuddy duddy evaporated and the watch assumed a completely different personality. For those of you starting to turn puce at this outrage, it was in this casual state of dress that I received only my second ever unsolicited compliment on my choice wrist wear from a complete stranger (in a John Lewis in York of all places).

Somehow, so equipped, the air of fuddy duddy evaporated and the watch assumed a completely different personality. For those of you starting to turn puce at this outrage, it was in this casual state of dress that I received only my second ever unsolicited compliment on my choice wrist wear from a complete stranger (in a John Lewis in York of all places).

If I have reservations about the bracelet, I have none about any other aspect of its aesthetics. The dial, as I’ve said is lovely, but I like it in particular because it is no shrinking, understated violet, but has a statement to make in the longitudinal brushing to the curved upper surfaces of the markers, and the pan pie delineation of the chapter ring sitting independent of the smaller inner circle of hour markers.

I love too the circular brush work to the upper surfaces of the lugs which then contrast with the slightly pregnant outward curve of the polished sides.

I love too the circular brush work to the upper surfaces of the lugs which then contrast with the slightly pregnant outward curve of the polished sides.

And of course, there’s the high-riding, sharp edge of the acrylic crystal emerging from the engine-turned bezel, lifting us above the iconic Rolex coronet sitting at the 12 marker.

And of course, there’s the high-riding, sharp edge of the acrylic crystal emerging from the engine-turned bezel, lifting us above the iconic Rolex coronet sitting at the 12 marker.

Where many men feel that anything less than 40 mm diameter in a watch is some sort of slur on their manhood, for me the perfect size is somewhere between 36 and 38mm. The DateJust sits at the lower end of that range but the beefy crown and long lugs lend it an air of masculine purpose that compensates just enough for its modest dimensions. That is a rather long-winded way of saying the proportions and size are just about perfect.

Where many men feel that anything less than 40 mm diameter in a watch is some sort of slur on their manhood, for me the perfect size is somewhere between 36 and 38mm. The DateJust sits at the lower end of that range but the beefy crown and long lugs lend it an air of masculine purpose that compensates just enough for its modest dimensions. That is a rather long-winded way of saying the proportions and size are just about perfect.

The Seiko is an altogether different proposition. The footprint is about the same, if a little shorter top to toe, and with its recessed crown at 4 establishing a slightly disturbing asymmetry to the arrangement of parts. The case is a riot of surfacing completely at odds with the 60’s vibe. From some perspectives it is breathtaking,

The Seiko is an altogether different proposition. The footprint is about the same, if a little shorter top to toe, and with its recessed crown at 4 establishing a slightly disturbing asymmetry to the arrangement of parts. The case is a riot of surfacing completely at odds with the 60’s vibe. From some perspectives it is breathtaking,

from others, its slab sides provide a beefier impression.

from others, its slab sides provide a beefier impression.

Where the Rolex makes such effective use of its bezel, the GS take a contrarian approach in dispensing with the bezel altogether, all the better to provide an unimpeded view of the wonderful dial and handset.

Where the Rolex makes such effective use of its bezel, the GS take a contrarian approach in dispensing with the bezel altogether, all the better to provide an unimpeded view of the wonderful dial and handset.

Where the Rolex uses rounded brushed markers, the Seiko’s are polished wedges rising to a cliff edge drop to the indexes of the chapter ring, which, in common with the Rolex, sits in its own track.

Where the Rolex uses rounded brushed markers, the Seiko’s are polished wedges rising to a cliff edge drop to the indexes of the chapter ring, which, in common with the Rolex, sits in its own track.

The hands are classic unlumed Seiko sword hands, with crisp beveled edges and pin sharp tips. Wonderfully judged, flawless design. Where the Rolex tops things off with its coronet, the Seiko asserts its branding with a floating metal SEIKO logo midway between the dial centre and the 12 marker, complemented and mirrored below by a gothic GS.

The hands are classic unlumed Seiko sword hands, with crisp beveled edges and pin sharp tips. Wonderfully judged, flawless design. Where the Rolex tops things off with its coronet, the Seiko asserts its branding with a floating metal SEIKO logo midway between the dial centre and the 12 marker, complemented and mirrored below by a gothic GS.

Side by side the Seiko somehow looks the fresher, more modern of the two but then its case was designed (at least) 20 years after that of the Rolex. The rightness of the Rolex design is embodied in its longevity: it parries the freshness, elegance and glamour of the GS with sheer class.

Side by side the Seiko somehow looks the fresher, more modern of the two but then its case was designed (at least) 20 years after that of the Rolex. The rightness of the Rolex design is embodied in its longevity: it parries the freshness, elegance and glamour of the GS with sheer class.

Interior

The DateJust is fitted with a 26 jewel 1575 automatic chronometer movement running at 19800 bph. The movement was introduced in 1965 and stayed in production I think until about 1977 but its roots can be traced back to the 1530 first introduced in 1957. In many ways, it is a very traditional, somewhat conservative movement but one with a couple of very neat tricks up its sleeve.

The Grand Seiko uses a chronometer spec. 35 jewel 6245 automatic also running at 19800 bph and also introduced in 1965 but based on a caliber dating to about 1960. Where the Rolex boasts hacking seconds and the facility to manually wind in power, the Seiko matches on the hacking front but lacks manual winding, countering instead with a quickset date feature.

The Grand Seiko uses a chronometer spec. 35 jewel 6245 automatic also running at 19800 bph and also introduced in 1965 but based on a caliber dating to about 1960. Where the Rolex boasts hacking seconds and the facility to manually wind in power, the Seiko matches on the hacking front but lacks manual winding, countering instead with a quickset date feature.

To be honest the lack of a quickset date on the DateJust is a bit of a pain in the neck if you wear it in circulation with other watches in a collection. The minor compensation is that you can wind the date forwards as well as backwards, which means you don’t need to cycle through more than 15 days to set the correct date. On paper then, the two movements seem well matched but in some key respects their design philosophy is very different.

The lesser of the two differences relates to the calendar function: in the Grand Seiko movement, the date changeover is driven by a date driving wheel which itself is driven by the hour wheel via an intermediate wheel. The date changes gradually over the course of a couple of hours as the finger on the date driving wheel makes contact with one of the inner teeth on the date dial. The whole process is regulated by the spring-driven date jumper.

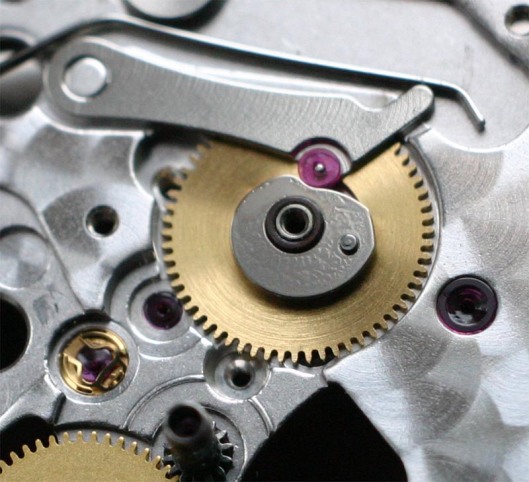

On the Rolex, the system operates in a similar way but the post on the date driving wheel that moves the date disk forward does so by the operation of a spring-loaded jeweled yoke operating against a cam mounted on the reverse side of the calendar wheel.

On the Rolex, the system operates in a similar way but the post on the date driving wheel that moves the date disk forward does so by the operation of a spring-loaded jeweled yoke operating against a cam mounted on the reverse side of the calendar wheel.

Photo credit: Archerwatches

At the critical moment, the jewel on the end of the yoke slips down the flatter side of the cam causing the calendar wheel to flick around and as it does so the post on the top side impacts on of the teeth on the inner side of the date disk. The date changeover occurs effectively instantaneously. You can get an idea of how it works from this photo of the sprung yoke and cam operating with the calendar wheel in a Rolex 3135. The arrangement is slightly different from that of the 1575 but the principle is the same.

It’s a neat trick and certainly a more sophisticated approach than the slow and steady changeover in the GS 6245A. Seiko did use a similar instantaneous date-change system in other contemporary movements at the time – for example the high beat 45 series movements used in manual wind King Seikos and Grand Seikos – but on this first automatic Grand Seiko they’d chosen to go with this highly refined iteration of the 62 series calibre.

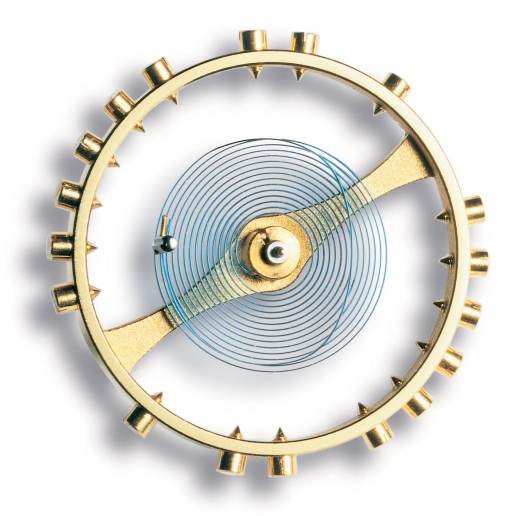

If that was the less significant difference, then what more does the 1575 have to bring to the table? If you compare the balances, the answer may present itself:

Photo credit for the lower image: http://www.luxurytyme.com

The Seiko uses a fixed-inertia balance with a hairspring whose length can be varied using the regulator. The hairspring passes through a pair of curb pins whose position marks the point at which the effective length of the hairspring is defined: moving the regulator arm away from the stud holder shortens the length of the hairspring and increases rate; moving it towards the stud holder lengthens the hairspring and slows the rate. The position of the stud holder affects symmetry of the hairspring coil and consequently controls the beat error – the extent to which the tick and the tock are evenly distributed about the harmonic swing of the oscillator. In other words the beat error defines the deviation from harmonicity of this harmonic oscillator. The clear advantage of such an arrangement is that regulation is a relatively straightforward business if you have access to a timegrapher. The disadvantage is that the hairspring breaths against the curb pins and consequently behaves differently depending on the positional attitude of the balance: the watch will display some positional variation in rate.

The Rolex balance you may be able to discern, has no regulator arm and the hairspring looks likes its been snagged on something. The lack of a regulator arm is because the 1575 uses a free sprung balance with a fixed length hairspring. The rate is controlled not by varying the length of the hairspring but by changing the inertia of the balance wheel. This is accomplished by moving weights screwed into the balance wheel either outward, which increases the inertia and slows the rate; or inward, which reduces the inertia and increases the rate – much as a spinning ice skater will speed up as they pull their arms in or slow down as they extend their arms outwards. The free sprung spring allows the balance to breath more freely and symmetrically rendering it less susceptible to positional variation in rate. The disadvantage is that regulation is a much fiddlier business requiring a special tool to move the screwed weights inboard or outboard.

The weird path taken by the hairspring is known as a Breguet overcoil. The hairspring is for the most part a traditional flat hairspring much like that of the Seiko but the end bends up over the top of the spring with its end then anchored much closer to the centre of the pivot point.

Breguet overcoil

The advantage of this arrangement is that the restoring force to the swing of the balance will be a much weaker function of mainspring power and consequently the time-keeping of the movement will be much less dependent on the state of wind. Generally, a fully wound movement exerts a greater force on the balance resulting in a larger amplitude; as the mainspring winds down, so the power decreases and the amplitude of the balance reduces which tends to speed the watch up. A Breguet overcoil allows the balance to maintain a much more consistent amplitude with varying mainspring power, thereby further improving the timekeeping.

How much difference does all of this make? Well the timekeeping of my 42 year old Rolex is exemplary – in the past 3 days for example, it has lost about four seconds. I’ve not worn the GS for a couple of weeks but the last time I checked its timekeeping on the timegrapher, it was running at 0 s/d with 0 ms beat error dial up but I have not gone through a full multi-position regulation and I’d be surprised if it is keeping time through the day as well as the Rolex (but you never know).

Conclusions

The bottom line with any comparison such as this is that it is rarely the specifications or performance that win the day. The winner is usually the one that speaks to you, that tweaks your soul a bit more, that lifts your spirits or, to paraphrase James May, the one that gives you that little bit of a tingle. Both of these watches are special. For me, some elements of the design of the Grand Seiko are just so beautifully judged that it seems unfair to sit it next to the more familiar, conservative DateJust. However, the Rolex has a compelling quality about every component that is hard to ignore: the movement for me is at another level; the finishing and sophistication of its design reflecting the fact that in 1968 it would have cost comfortably more than double that of the GS. I could chicken out and call it an honorable draw, but I won’t: for me the winner by a nose is the Rolex but then this was never really a fair fight. I suspect a rematch with contemporary watches from 2015 might go the other way.

What a wonderful, erudite, and well-thought analysis of two heavy-hitting watches. Refreshing, too, given the bombastic back-and-forth one reads on fora whenever Seiko and Rolex are spoken of in the same breath. Here, we have an editorial of sorts, but one that is backed by a solid knowledge of the technical aspects of what you are talking about. There is real substance in this piece–in both the aesthetic and mechanical–which shows a deep understanding beyond most of our ken, especially mine. I thank you for your passion and intellect and taking such time and pains of sharing it. I would look forward to a head-to-head comparison of two more recent incarnations of these watches.

Curtis, thank you. Your appreciation is very welcome. I’d love to do a similar head-to-head with recent incarnations but fear I am unlikely ever to able to afford to do so!

Martin

And I as well, sir. I as well. Had I the means and the watches, I would lend you mine, for scholarly purposes of course.

Really enjoyed this, especially after owning an Oysterquartz and going to get myself a SBGV009. Keep up the good work and happy new year!:)

Thank you. I am glad you enjoyed it.

Your analysis is very thorough yet, ironically, your quoting of James May sums up the whole luxury watch business. It is the watch that gives YOU a tingle that is the right one for YOU. I have been fortunate to have owned two Omegas, three Rolexes and currently have a Grand Seiko. The Swiss watches were all superb but it is the Seiko that I know I will never part with. When I bought each of them I thought that they were the ultimate ( within my budget) but as I have aged, I am content not to have to display my wealth . The Grand Seiko can be mistaken for something much less expensive at first glance. It is only close inspection that reveals it to be a truly exceptional timepiece.

Wonderful writing!

Thank you!

Excellent constructive review and if I come into some money my target is Grand Seiko Spring Drive.

Hello there, awesome article!! I am an amateur learning watchmaking online. Here the Rolex spoke to me, what a beauty. Have you written an article comparing modern Rolex vs GS?

Hi Christian,

Thanks for the nice comment. I’ve not been able to do a repeat performance for the modern equivalents because, while I do have a modern Grand Seiko Quartz (see here), I do not own any other Rolex and with the way prices are going at the moment, I don’t see that happening. I should probably add that there are currently no modern Rolex that I aspire to own. I would not say no to a 16610 or GMT Master from that period, but the squared off ceramic stuff leaves me completely cold.

I own a Seiko kakume blue speed timer 6138 0030 passed down from my father which was gifted to him by my grand father. Its more than 40 years old and still keeping the time. I treasure it and hoping to pass it down to the next generation. A great watch with full of memories.

This was delightfully educational, and while objective still made allowance for subjective evaluation.

You don’t mention water-resistance. Some Rolex owners swim with, sweat on, and otherwise bump their datejusts about. Datejusts handle this very well. But how waterproof are the Grand Seikos? Lesser sports Seikos are good at resisting such adventures, but is the GS as well-sealed as the Rolex?

The only real difference between the two is the twin lock screw down crown on the Rolex which should offer superior water resistance to the 62GS crown. However, the GS is rated at 50m and so, given that both watches were aimed at the dressier end of the market, I don’t see that being a limitation for most buyers.