In reflecting on the impact of Japanese watchmaking through the 1960’s and 70’s it is all too easy to overlook the contributions of the Citizen Watch Company. Seiko has maintained a presence in the collective horological consciousness throughout the past 60 years as the pre-eminent Japanese watch company, and throughout that period has produced an embarrassment of riches, albeit alongside a fairly impressive volume of chaff. Citizen’s role as the second-tier Japanese watch producer sustained through the ’60’s and ‘70’s, accounting for about 30% of Japanese watch production but by the mid-1980’s, Citizen had passed Seiko in terms of volume to become the world’s largest watch company.

In spite of its almost vanishingly small international profile through the 1950’s and ‘60’s, Citizen nonetheless attracted attention in Japan for a number of technological firsts: with the development of the proprietary Parashock setting, it produced Japan’s first shock-resistant watch in 1956, although the extent to which it pipped Seiko to the post in this innovation is probably measured in weeks; it produced the first Japanese alarm watch from 1958 (a full 8 years before the appearance of the Bell-Matic); the first Japanese Electronic wristwatch in 1966; and in the Parawater of 1959, it produced Japan’s first water-proof watch, a year or so before the Seiko Cronos Seahorse.

Citizen and Seiko both released their own proprietary anti-shock designs in 1956 (Parashock and Diashock, respectively) and their first waterproof watches, the Parawater (1959) and Cronos Seahorse (arguably also 1959 but possibly a year or so later).

I freely confess that up to this point, my knowledge of vintage Citizen wristwatches was limited, to say the least, but one or two designs have caught my eye over the years, and one in particular has inveigled its way into my affections and become a covert object of desire. The watch in question is a descendant of that first Parawater of 1959. My inclination to seek out and acquire one has been tempered by my ignorance of the Citizen vintage market, the vastly less abundant sources of information on the internet and the patent difficulty in sourcing parts. Nevertheless, a few months ago, my interest was piqued by an auction for a Citizen シチズン Super Crystal Date スーパークリスタルデイト 33石 PARA 150M WATER AUDS52801-Y. Quite a mouthful but the accompanying photographs were excellent and suggested a well-used but honest watch.

There were 33 bids for this one, mine the 33rd and I seemed therefore to have secured my prize. A couple of weeks later the watch arrived and I was able to reassure myself to some small extent that my impulse had not been entirely foolhardy.

The translation of the description accompanying the auction suggested that ‘Scratches on the glass are many’. No kidding. The condition of the crystal is entirely consistent with that of the case, but the excellent condition of the dial and hands suggested that no calamities had befallen this watch and that its water-proof credentials have held up.

The translation of the description accompanying the auction suggested that ‘Scratches on the glass are many’. No kidding. The condition of the crystal is entirely consistent with that of the case, but the excellent condition of the dial and hands suggested that no calamities had befallen this watch and that its water-proof credentials have held up.

My main concern at this point was the question of parts, in particular locating a replacement crystal. This undertaking is not helped by the fact that there is almost no information at all about casing parts for this model and so I would be having to make some extrapolations based on similarities in the case construction with that of contemporary Citizen 150m diver’s watches.

The serial number on the watch, beginning 704xxx, indicates a manufacture date of April 1967 and its model number of AUDS-52801 suggests some familial relationship to the SADS-52801 unibody divers and/or the conventionally constructed AUDS-52802. I have to say that I find the model numbering of these vintage Citizens utterly bewildering but all three of these models appear to feature very similar pronounced flat top, inner dome glass crystals. My opening gambit therefore is that any crystals advertised as being suitable for this family of 150m diver’s watches may do the trick, as long as the diameter is the same as that of the crystal fitted to my watch. I can’t measure the diameter until the crystal is out and so, because this is a uni-body design, the next step is to remove the bezel, which we discover also serves as the crystal retaining ring.

A number of aspects of this watch are reminiscent of the Seiko 6105, not least of which the shape of the crystal and the manner in which it is secured into the case. In contrast to the 6105, which employs a single L-profiled crystal gasket, the Parawater uses two gaskets, a flat gasket sitting beneath the crystal and an o-ring to provide an additional seal around its outer edge.

A number of aspects of this watch are reminiscent of the Seiko 6105, not least of which the shape of the crystal and the manner in which it is secured into the case. In contrast to the 6105, which employs a single L-profiled crystal gasket, the Parawater uses two gaskets, a flat gasket sitting beneath the crystal and an o-ring to provide an additional seal around its outer edge.

The o-ring has seen better days but the flat gasket looks in fine condition still, hopefully requiring just a clean. The flat gasket sits around the outer edge of a chromed chapter ring and so next we remove the flat gasket before extracting the chapter ring.

The o-ring has seen better days but the flat gasket looks in fine condition still, hopefully requiring just a clean. The flat gasket sits around the outer edge of a chromed chapter ring and so next we remove the flat gasket before extracting the chapter ring.

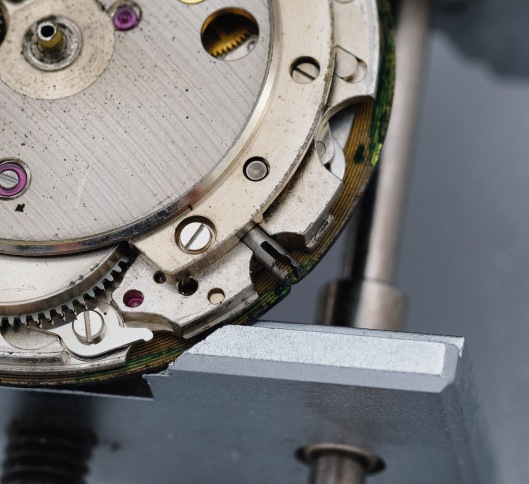

Given that I was proceeding without the benefit of any experience at all in working with these watches and in the absence at this point of any technical manuals, the next step required a little thought. You will see that I’ve aligned the hands in preparation for their removal and so that is what I did next. How then to remove the movement? There is no room to insert any sort of tool to depress a setting lever, if any such lever had made its presence known. The crown must be two-part and so my options reduced to either pulling the crown or assuming that the coupling is sufficiently loose to allow the movement to fall out once the coupling is aligned perpendicular to the dial plane. I elected to go for the latter approach and sure enough, some juggling of the inverted case whilst rotating the crown saw the movement fall out without too much difficulty.

Given that I was proceeding without the benefit of any experience at all in working with these watches and in the absence at this point of any technical manuals, the next step required a little thought. You will see that I’ve aligned the hands in preparation for their removal and so that is what I did next. How then to remove the movement? There is no room to insert any sort of tool to depress a setting lever, if any such lever had made its presence known. The crown must be two-part and so my options reduced to either pulling the crown or assuming that the coupling is sufficiently loose to allow the movement to fall out once the coupling is aligned perpendicular to the dial plane. I elected to go for the latter approach and sure enough, some juggling of the inverted case whilst rotating the crown saw the movement fall out without too much difficulty.

We are presented with an example of the 5410 automatic calibre, a sophisticated 33 jewel movement running at 18000 bph and featuring hand-winding, seconds hacking, an integrated autowinding mechanism and quickset date complication. This movement is a member of the 52 series (remember, the model number is AUDS-52801) but is designated 54 to indicate that it employs date-only calendar rather than day/date.

We are presented with an example of the 5410 automatic calibre, a sophisticated 33 jewel movement running at 18000 bph and featuring hand-winding, seconds hacking, an integrated autowinding mechanism and quickset date complication. This movement is a member of the 52 series (remember, the model number is AUDS-52801) but is designated 54 to indicate that it employs date-only calendar rather than day/date.

You’ll notice that the winding weight is missing. That is because it was already detached and had remained sitting in the base of the case.

This would certainly explain why the watch might have been set to one side, the automatic mechanism no longer working. If you look at the inner case tube, you will see the male end of the split stem poking through. The female counterpart is still located in the movement.

This would certainly explain why the watch might have been set to one side, the automatic mechanism no longer working. If you look at the inner case tube, you will see the male end of the split stem poking through. The female counterpart is still located in the movement.

The crown is non-screw down, much like the first generation 6105 and in common with that crown, features a captured gasket, sitting behind a crimped-in washer. The gap is far too small to offer any hope at all that the gasket may be extracted without first removing the washer, but the gasket itself appears supple, retaining a sphincter-like grip on the crown tube. Given the dearth of spare parts for these watches, I am inclined simply to clean the crown and hope that the residual water resistance is at least up to the job of keeping at bay the odd splash whilst cycling in the rain.

The crown is non-screw down, much like the first generation 6105 and in common with that crown, features a captured gasket, sitting behind a crimped-in washer. The gap is far too small to offer any hope at all that the gasket may be extracted without first removing the washer, but the gasket itself appears supple, retaining a sphincter-like grip on the crown tube. Given the dearth of spare parts for these watches, I am inclined simply to clean the crown and hope that the residual water resistance is at least up to the job of keeping at bay the odd splash whilst cycling in the rain.

Let’s press on with the movement, starting by removing the dial.

Let’s press on with the movement, starting by removing the dial.

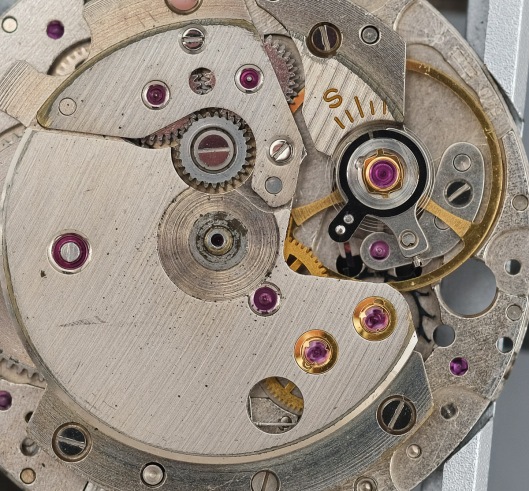

In surveying the calendar side of the movement, we note the characteristic Parashock setting serving the balance arbor and two capped jewel settings that resemble small-scale Diashock settings and which serve the escape wheel and fourth wheel. We can also see the jeweled barrel arbor bearing, a sure sign of a quality movement. Before pressing on, I also note that two of the screws are annodised black, suggesting perhaps that they are left-threaded.

In surveying the calendar side of the movement, we note the characteristic Parashock setting serving the balance arbor and two capped jewel settings that resemble small-scale Diashock settings and which serve the escape wheel and fourth wheel. We can also see the jeweled barrel arbor bearing, a sure sign of a quality movement. Before pressing on, I also note that two of the screws are annodised black, suggesting perhaps that they are left-threaded.

The mechanism on this side certainly has that air of mid-1960’s engineering in which complex solutions to achieving particular functionality are a mark of pride. In breaking down the calendar parts, I encounter the first of numerous small springs, any one of which threatens to leap into oblivion at the flap of an Amazonian butterfly wing.

The spring pictured in the upper left photo is pressing against the date corrector finger whose correct direction of action is achieved by means of a clutch wheel sitting beneath.

The spring pictured in the upper left photo is pressing against the date corrector finger whose correct direction of action is achieved by means of a clutch wheel sitting beneath.

I’ve never encountered this approach before – very clever and rather neat! Dismantling calendar side further reveals the first patently broken part.

I’ve never encountered this approach before – very clever and rather neat! Dismantling calendar side further reveals the first patently broken part.

The tip of the setting lever that is supposed to engage with the yoke has snapped clean off. This will clearly need a new setting lever and where normally that would have presented a difficulty, my sub-conscious foresight will save the day. Time to flip the movement over and survey the balance side.

The tip of the setting lever that is supposed to engage with the yoke has snapped clean off. This will clearly need a new setting lever and where normally that would have presented a difficulty, my sub-conscious foresight will save the day. Time to flip the movement over and survey the balance side.

Lots to take in here but I’ll note the congregation of grot in the vicinity of the autowinder pivot, perhaps having contributed to wear that resulted in the detachment of the weight.

Lots to take in here but I’ll note the congregation of grot in the vicinity of the autowinder pivot, perhaps having contributed to wear that resulted in the detachment of the weight.

The Parashock setting sign-posts quite clearly what is required to remove the cap jewel and so I rotate the tab towards the cut-out and the spring pops up gently, inviting extraction.

The cap jewel is an integral part of the shock spring, much like the Breitling shock setting we met in the Top Time project (see photo here). Beneath the cap jewel sits the pivot jewel, supported within a removable spiral spring. You can get a better idea of how the parts are arranged from the figure below taken from a Citizen technical manual.

The cap jewel is an integral part of the shock spring, much like the Breitling shock setting we met in the Top Time project (see photo here). Beneath the cap jewel sits the pivot jewel, supported within a removable spiral spring. You can get a better idea of how the parts are arranged from the figure below taken from a Citizen technical manual.

The Citizen equivalent of Diafix settings are called Profix and, in common with Diafix, serve the purpose not of providing shock protection but of oil preservation. In the 5410 movement, Profix settings are used for the escape wheel and fourth wheel.

The Citizen equivalent of Diafix settings are called Profix and, in common with Diafix, serve the purpose not of providing shock protection but of oil preservation. In the 5410 movement, Profix settings are used for the escape wheel and fourth wheel.

I have to say, I prefer the Citizen approach to the infuriating Seiko Diafix settings. You may also have noticed in the photo above that this movement employs a double third wheel, identical in its function to that used in the Seiko 5106. You can read more about how these double third wheels work in the Seikomatic-P post here.

I have to say, I prefer the Citizen approach to the infuriating Seiko Diafix settings. You may also have noticed in the photo above that this movement employs a double third wheel, identical in its function to that used in the Seiko 5106. You can read more about how these double third wheels work in the Seikomatic-P post here.

Next on our schedule is the integrated autowinding mechanism. Having first removed the automatic train bridge, we meet the first three components of the gear train that transmits the winding action of the rotor to the barrel. The three gears you see comprise the intermediate pawl winding wheel (capped with the screw head) and the two pawl winding wheels, one of which transmitting clockwise motion of the rotor and the second anticlockwise.

The additional pawl winding wheel is fitted with a pinion on its lower side that meshes with the reduction gear that you can see beneath the train bridge. This in turn transfers power to the barrel ratchet wheel via the driving gear for the ratchet wheel. You should be able to get a sense of how this all works from the figure below.

The additional pawl winding wheel is fitted with a pinion on its lower side that meshes with the reduction gear that you can see beneath the train bridge. This in turn transfers power to the barrel ratchet wheel via the driving gear for the ratchet wheel. You should be able to get a sense of how this all works from the figure below.

We are now free to remove the train bridge, exposing the power train from barrel to escape wheel.

The power transmits as follows:

The power transmits as follows:

You can see that the third wheel plays two roles, transmitting power from the centre wheel to the sweep second pinion and then from the sweep second pinion to the fourth wheel. Again, clever design.

You can see that the third wheel plays two roles, transmitting power from the centre wheel to the sweep second pinion and then from the sweep second pinion to the fourth wheel. Again, clever design.

Back to the source of that power and the barrel, now inverted and exposing the ratchet wheel, mounted unconventionally between the bottom of the barrel and the main plate.

The final detail before completely denuding the main plate is the hacking lever mechanism, whose action is accomplished by a pointed sliding stop lever pushing up against the stop lever spring which in turn then makes contact with the outer circumference of the fourth wheel.

The final detail before completely denuding the main plate is the hacking lever mechanism, whose action is accomplished by a pointed sliding stop lever pushing up against the stop lever spring which in turn then makes contact with the outer circumference of the fourth wheel.

The mainspring looked much like any number of mucky Seiko mainsprings I’ve encountered over the years but it did look a little over-packed, in particular the arrangement of the bridle against the inner wall of the barrel, appearing to bunch the coils slightly and distorting the symmetry of the spring.

The mainspring looked much like any number of mucky Seiko mainsprings I’ve encountered over the years but it did look a little over-packed, in particular the arrangement of the bridle against the inner wall of the barrel, appearing to bunch the coils slightly and distorting the symmetry of the spring.

I was a little concerned about this but I have a couple of spare 52 series movements and took a quick look at one of their mainsprings and it looked identical. With a shrug, I set about removing the mainspring with a plan to reuse it.

I was a little concerned about this but I have a couple of spare 52 series movements and took a quick look at one of their mainsprings and it looked identical. With a shrug, I set about removing the mainspring with a plan to reuse it.

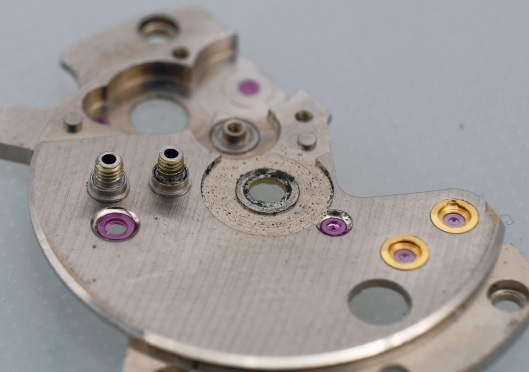

Plenty of spring in its step still by the look of it. Two matters require attention before I start the cleaning process, both of which on the barrel and train wheel bridge. The first of these was flagged by the separation of winding weight from its post prior to removal of the movement from the case. I suspected this might have been facilitated by wear to the thread on the post and indeed this turns out to be the case.

Plenty of spring in its step still by the look of it. Two matters require attention before I start the cleaning process, both of which on the barrel and train wheel bridge. The first of these was flagged by the separation of winding weight from its post prior to removal of the movement from the case. I suspected this might have been facilitated by wear to the thread on the post and indeed this turns out to be the case.

The second issue was that the jewel serving one of the pawl winding wheels was chipped and needed replacing.

The second issue was that the jewel serving one of the pawl winding wheels was chipped and needed replacing.

I’ve alluded to my possession of a couple of spare 52 series movements already but this happy state of affairs is the result not of any prescience on my part but of complete chance. In fact, prior to breaking into the watch described here, I had no clue that the Citizen movements I had already would be suitable parts donors. It is just blind luck that they are. The two movements in question came as part of a massive bargain box of bits I snagged a few years ago, the contents of which have saved my bacon on numerous occasions. Sometimes, the gods smile down upon us. One of the spare barrel and train bridges in my parts repository was in a position to donate both the required jewel as well as the rotor post. You might ask why I didn’t just replace the whole bridge but both of the donor movements are 27 jewel 5203’s that use a steel bearing for one of the pawl winding wheels. The donor jewel was perfect, and it fitted without drama in place of the now extracted, damaged original.

I’ve alluded to my possession of a couple of spare 52 series movements already but this happy state of affairs is the result not of any prescience on my part but of complete chance. In fact, prior to breaking into the watch described here, I had no clue that the Citizen movements I had already would be suitable parts donors. It is just blind luck that they are. The two movements in question came as part of a massive bargain box of bits I snagged a few years ago, the contents of which have saved my bacon on numerous occasions. Sometimes, the gods smile down upon us. One of the spare barrel and train bridges in my parts repository was in a position to donate both the required jewel as well as the rotor post. You might ask why I didn’t just replace the whole bridge but both of the donor movements are 27 jewel 5203’s that use a steel bearing for one of the pawl winding wheels. The donor jewel was perfect, and it fitted without drama in place of the now extracted, damaged original.

The winding post incorporates the jeweled bearing to its rear for the sweep seconds pinion and is an interference fit. Its removal is accomplished using a jeweling tool.

The winding post incorporates the jeweled bearing to its rear for the sweep seconds pinion and is an interference fit. Its removal is accomplished using a jeweling tool.

In the photo below you will see the worn post (right) sitting next to its replacement (left).

In the photo below you will see the worn post (right) sitting next to its replacement (left).

I decided to clean the bridge and new post separately before refitting and so we find ourselves at the half-way point in proceedings.

I decided to clean the bridge and new post separately before refitting and so we find ourselves at the half-way point in proceedings.

I am conscious that some of you may be flagging and so this may be an appropriate point to pause for breath, have a cup of tea and reflect on the ingenuity of human invention. The concluding part can be found here.

Lovely watch! What is the case diameter?

I have a Citizen 7 Star Parawater 4-520343 Y which is with Adrian Sellick in Australia receiving some ‘love’ as it wasn’t in good repair (I like a little patina on my vintage watches, it’s part of the watch’s history).

I’m a confirmed Seiko fan, specifically the 60s-80s Dive Watches, but every now and then, like the Seven Star Parawater, Citizen throws up a cracker.

Have you ever come across the Citizen 7 Star Parawater 4-520343 Y and if so, will you do a piece on one?

Looking forward to Part 2!

Hi Stephen,

The watch is 37.5mm diameter, not including the crown and so in my book, the perfect size. This is the first vintage Citizen I’ve worked on and I hope not the last and so there is a reasonable chance Citizen watches of this era may feature in the future. However, I am on a self-imposed watch purchasing hiatus while I work my way through the mountain of waiting projects and so if I do turn my attention to Citizen again, it won’t be for a while yet. Part 2 should appear this evening.

hello

thank you so much for this !

do you have replaced the crystal ?

do you have thé citizen part number for it ?

Yes, I replaced the crystal with an original, part number 54-51810.

As a committed vintage Seiko addict, I have recently come under the spell of a Citizen Jet Auto Dater. As vintage Seiko prices rise, the early Citizen watches from the 60’s are still quite affordable and good value for the money. The Jet automatic movement is pretty amazing and unique. Not sure Citizen watches will ever gain the following of vintage Seiko’s but they are still a very nice and interesting watch.

I agree. They are really appealing watches with lovely movements. The problem from my perspective is the scarcity of parts and general lack of other resources. Seiko will always have a huge advantage in that respect.